Target setting for nitrogen use efficiency in Scotland

Research completed March 2024

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/5316

Executive summary

Background

The Scottish Government’s Climate Change Plan Update (CCPu) sets out an ambition for the agriculture sector to reduce emissions by 31% from 2019 levels by 2032, and a commitment to “work with the agriculture and science sectors regarding the feasibility and development of a SMART target for reducing Scotland’s emissions from nitrogen (N) fertiliser.”

The agricultural sector is dependent on N inputs, both organic and inorganic. The inefficient use of these inputs creates N wastage, impacting air and water quality and the climate. The global nature of the issue provides an opportunity for Scottish agriculture to learn from other countries on how to improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE), i.e. taking action to reduce agricultural N losses while maintaining and supporting the sector in terms of income and yield.

This report explores the potential for setting a NUE target for agriculture in Scotland. It examines N flows found in Scottish agriculture as shown in the Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet (SNBS), providing a clear analysis of the opportunities and barriers.

Key findings

Whilst there is theoretical potential for setting a NUE target for Scotland, there are practical obstacles that policy makers would need to overcome for the target to be implemented.

This research argues sector specific NUE values are not currently feasible due to the calculation set-up in the SNBS and the assumption that production will remain stable, with only inputs decreasing.

- We suggest that the SNBS calculations need refinement to attribute flows of N to the different measures and sectors. In the current version of the SNBS, the NUE calculations do not align directly with what happens in practice because there are overlaps and movements of N flows between the different agricultural sectors.

- These are not easily viewed in isolation and not necessarily attributed to the correct sector. For example, mitigation measures around manure management will, in practice, be mainly implemented by the livestock sector but will, in the current calculations, be attributed to the arable sector because they are linked to reduced emissions from spreading of organic matter to soils.

Opportunities

- The SNBS would offer an effective data source for setting and monitoring progress towards a single nationwide NUE target that covers all sectors.

- Many mitigation measures with known impacts on reducing N waste and improving N use are already in use in Scotland. Measures with the greatest potential improvement on NUE are

- nitrification inhibitors

- improving livestock nutrition, and

- improving livestock health.

- Note – that the improvement reflects implementing the relevant measure individually and does not consider any combination effects or interactions with other measures.

- The lowering of N-related emissions through reaching a NUE target will positively contribute to other emission reduction targets and the potential for an increase in farm business profitability.

Barriers

- Since a sector specific NUE target is currently not feasible, the remaining option is a single nationwide target.

- However, the arable, horticultural and livestock sectors would need to implement distinct mitigation measures, start from differing baselines, and will react inconsistently to implemented changes. This is partially due to the current limitations in the SNBS, but also due to the much lower baseline of current NUE values, setting a nationwide NUE target might cause the livestock sector to feel unfairly targeted.

- Some mitigation measures require significant capital expenditure to implement.

- The concept of NUE is complex and clear communication is required to ensure that targets and measures are clearly understandable and achievable to generate support from the farming sector.

- We examined different scenarios to model a potential target. The table below shows an achievable target and one that is more ambitious. The 2045 (Ambitious) scenario is based on transformational change across the sector.

|

Potentially achievable NUE estimates (%) | |||||

|

2021 (Current) |

2030 |

2040 |

2045 |

2045 (Ambitious) | |

|

Whole agriculture |

27.2 |

33.7 |

35.7 |

38.2 |

40.9 |

- No country currently uses a standalone NUE target. Several countries have set N-related targets, some of which include information on NUE. Notably, the Colombo Declaration represents the first time that governments are collaborating on a global N management target on N waste.

Conclusions and recommendations

While this research identified opportunities for setting a NUE target for Scottish agriculture, more work is needed to fully understand the following elements:

- differential flows for each sector

- make appropriate changes to the SNBS

- ensure that the role of legumes in emissions reduction is fully integrated and

- carefully plan communication to achieve support from the farming sector.

A NUE target is not currently the most appropriate option for Scotland. This is partially due to the methodology in the current SNBS.

Recommendations

- Explore the potential for a more granular breakdown, and accurate representation of N flows in the SNBS. This may be difficult but would significantly help both monitoring and setting of a SMART NUE target.

- Creating a NUE target requires considering several criteria including mitigation measures, current uptake, applicability, expected future uptake, timescales, and sector breakdown. It is important to understand that other agricultural practices may impact N flows, as will changes in the size of agricultural sectors, and achieving these targets in practice will require supporting instruments to encourage the uptake of these measures. This research recommends that:

- N waste be considered as a target instead of a NUE target and that a SMART analysis is carried out to explore a N waste target further. Opportunities for setting a N waste reduction target include:

- It is an easier concept to communicate to the farming community.

- It values any N as a resource until it is lost as waste, creating options for greater collaboration between the arable, horticulture and livestock sectors. Any potential bias towards a sector will be avoided.

- A N waste target would achieve reductions in national NUE thereby achieving the same objectives without the current issues around NUE targets.

- Experience of the United Nations Environment Assembly and the Green Deal’s Farm to Fork targets has shown more potential in successfully reducing N pollution when focusing on reducing N waste over NUE targets as a policy option.

- If a decision is made to set a NUE target, the underlying assumptions should first be updated based on latest available evidence, for example using the updated Up to date Farm Census data. would strengthen any underlying assumptions and may directly influence the potential for the mitigation measures, particularly relating to slurry and manure management.

- The SNBS be improved by assigning distinct N flows to N waste and N re-use. A SMART target analysis for N waste will be beneficial to set a challenging and realistic target.

Glossary / Abbreviations table

Table 1: Glossary/ abbreviations table

|

Term/acronym |

Definition |

|

CCPu |

Climate Change Plan Update |

|

CO2 |

Carbon Dioxide |

|

EUNEP |

European Union Nitrogen Experts Panel |

|

GHG |

Greenhouse gas |

|

INMS |

International Nitrogen Management System |

|

kt N / yr |

kilo tonnes of nitrogen per year |

|

MtCO2e |

Million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent |

|

N |

Nitrogen |

|

N2 |

Di-nitrogen |

|

NH3 |

Ammonia |

|

NH4+ |

Ammonium |

|

NO3– |

Nitrate |

|

N2O |

Nitrous Oxide |

|

NUE |

Nitrogen Use Efficiency |

|

NVZ |

Nitrate Vulnerable Zones |

|

PESTLE |

Political, Economic, Social, Technical, Legal, Environmental |

|

REA |

Rapid Evidence Assessment |

|

SNBS |

Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet |

|

SWOT |

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

|

UNEP |

United Nations Environment Program |

Introduction

Nitrogen and its relevance to agriculture

An excess of N can both directly and indirectly lead to soil, water and air quality deterioration which is detrimental to human and ecosystem health (e.g., affecting respiratory systems and reducing oxygen in water). According to the IPCC AR5 Synthesis Report, N2O has a global warming potential (GWP) 273 times that of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 100-year timescale. In Scotland N2O is responsible for a quarter of the agriculture sector’s total GHG emissions.

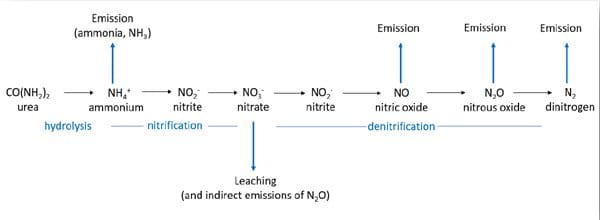

More detail can be found in Appendix A on the process of leaching, the effects of eutrophication and how N2O and NH3 are emitted from agricultural sources and in Appendix B on the chemical processes of N conversion.

Nitrogen Use Efficiency

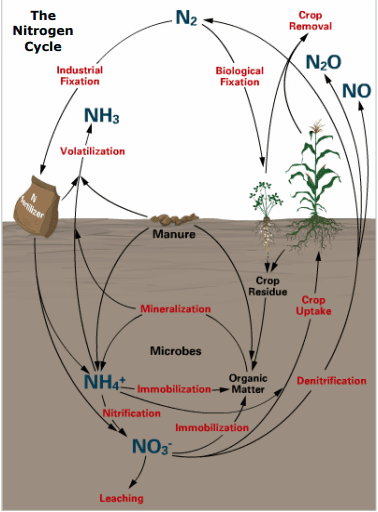

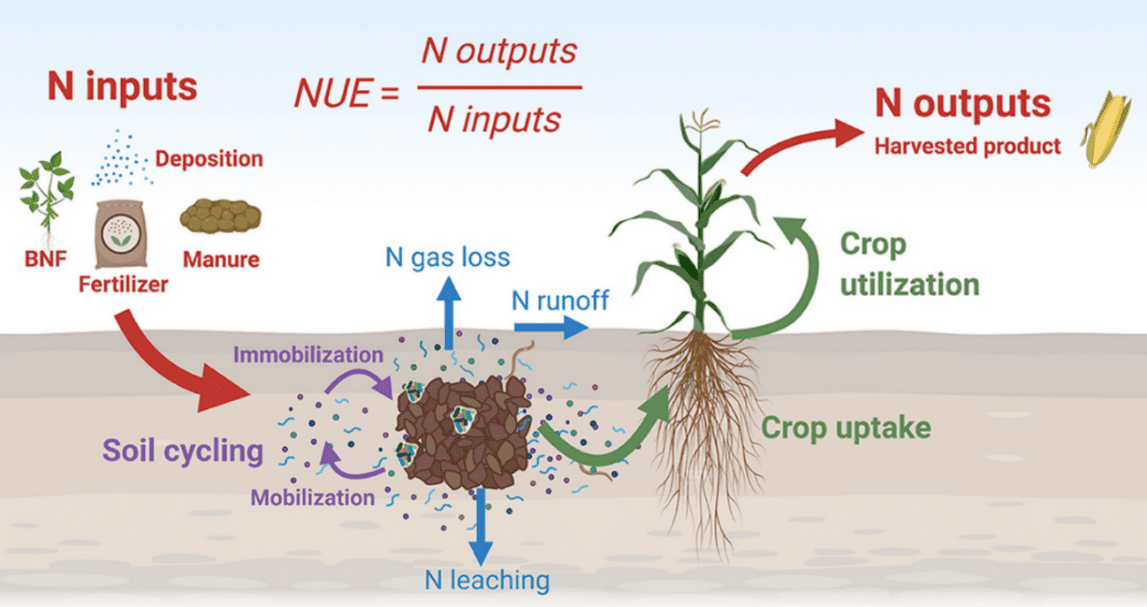

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) describes the ratio between total N input (e.g., fertiliser) and total N output (e.g., harvested product) expressed as a percentage (%). Figure 2 presents a visual example of NUE.

Figure 2. NUE diagram. Source: Udvardi et al., 2021

NUE gives an indication of the efficiency of crop utilisation of N. Generally, the higher the percentage NUE the better as this means less loss of N to air and water and indicates the crop is efficient in the uptake of N. However, pushing the ratio too high (for example over 90% in a cereal crop) can indicate ‘soil nutrient mining’ leaving not enough available N to maintain healthy crop growth and soil ecosystems (Sanchez, 2002). When NUE is too low (less than 50% in cereal crops), a large amount of N is likely being lost to the water and air. An ideal NUE would therefore be between 50% and 90%. NUE efficiency is also greatly impacted by climatic conditions, with changes in microbial activity in drought and frozen soils, along with increased risk of denitrification or leaching when soils are waterlogged.

NUE values are therefore both indicators of resource efficiency and markers for improvement. Key factors influencing NUE include crop type and rotation, soil pH and texture, climate, ammonia, leaching, biological utilisation of N and N management amongst others. As such, an absolute NUE reference value cannot be universally applied and will need to be understood and optimised for specific systems.

Nitrogen and NUE targets in other countries

Introduction

A Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) seeking evidence relating to the setting and use of nitrogen and NUE targets was undertaken and identified peer-reviewed academic literature as well as government policies and websites. The review also identified grey literature sources such as farming and industry press reports. This search included, but was not limited to, targets for NUE, N emissions and N fertiliser use. The methodology can be found in Appendix C. The review focussed on identifying:

- Relevant scientific research on NUE target setting (4.2)

- Countries with N-related target/s, including types, values and timeframes (4.3)

- Relevance to Scottish agriculture, agricultural sectors and N flows (4.4).

Research on NUE target setting

This section includes information found through the REA on global NUE trends and relevant scientific research on the possibility of setting a NUE target including the necessary considerations (e.g., differences in farming sectors). 95 sources of literature were reviewed through the REA, 38 of which were from the UK, 32 from European countries and the remaining from other countries from around the world. Search strings used to gather this data can be found in Appendix C.

The NUE trend in the UK shows an increase from 1961 to 2014 (Lassaletta, L et al., 2014) which is likely a response to both regulation and market forces (for example the Nitrates Directive and changes in farm incomes). A full list of country-specific changes (%) in NUE values from 1961 to 2014 can be found in Appendix D. Following on from these observations, the research discussed below highlights the requirements and considerations for setting a NUE target.

Studies such as Quemada et al., 2020 collected farm-level data from 1240 farms across Europe and through statistical analysis, present NUE targets for different agricultural systems (e.g., 23% for a pig farm and 61% for an arable farm) which demonstrates the possibility of setting farm-level NUE targets. However, the study also highlights the importance of how differences in farming sectors will impact target setting.

A study conducted by Antille et al., 2021 states that there is no universal method for the calculation and reporting of NUE across all agricultural sectors. Furthermore, research projects which provide recommendations for NUE targets also suggest that such targets could be dependent on the agricultural system and its management, as well taking the ‘4R nutrient stewardship’ approach (right fertilizer type, right amount, right placement and right time) (Waqas et al., 2023). These approaches are country and region specific, dependent on climate, farmer knowledge, technological advancement and availability.

The EU Nitrogen Experts Panel (EUNEP) (initiated by an industry-based organisation ‘Fertilizers Europe’) recommends a maximum NUE of 90% (Duncombe, 2021), with an ‘ideal range’ of 50% to 90%. This range has been set to reflect that a NUE value below 50% is likely to result in N lost to the environment, while a value above 90% could result in soil N mining. Further detail is given in section 3.2. Whilst it is important to note that values will vary according to context (soil, climate, crop etc), the identification of this ‘ideal range’ by the EUNEP helps us to understand the opportunity and potential for setting a NUE target.

The research has highlighted that whilst it is possible to set NUE targets, there are a number of variables which impact upon setting a NUE target. These variables include the differences in farming sectors, differences in farming management, a lack of universal calculation and reporting of NUE, country / region specificity and climate.

N targets by country – types and policy context

There are currently no standalone country level NUE targets. Several countries, however, have set N targets through various means, some of which include information or actions on NUE. The review of approaches and literature can be summarised as having three main reasons/drivers for introducing N targets, these are all focused on responding to environment and climate impacts of N emissions:

- To lower GHG emissions

- To improve water quality

- To improve air quality

The underlying impact of N-related targets all seek to reduce N waste[1], however, the two primary mechanisms differ in their points of measurement. Some targets are set to reduce N emissions whilst others are set to improved water or air quality. Table 2 gives an overview of existing initiatives across the world and their main N target with relation to agriculture. Many are relatively vague and reflect the difficulty in setting firm policy across regions or countries. No set value was found for the targets in table 2 that do not include a percentage or numeric change. These initiatives or legislation are described in further detail below.

Table 2. Overview of existing initiatives on N targets.

|

Initiatives and country |

N target |

|---|---|

|

Colombo Declaration 2019, United Nations Environment Programme |

Halve N waste by 2030 |

|

Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019, New Zealand |

Reduce N2O emissions to net zero by 2050 |

|

Nitrates Directive 1991, EU |

Reduce NO3 losses from agricultural sources |

|

National Emissions reduction Commitments Directive 2016, EU |

Reduce NH3 emissions from agriculture |

|

Farm to Fork Strategy 2020, EU |

Reduce nutrient losses by at least 50% |

|

Harmony rules, Denmark |

Limit N inputs to land from livestock manure |

|

Climate Action Plan 2021, Ireland |

Improve NUE |

|

Green transition of the agricultural sector 2021, Denmark |

Reduction of N emissions by 10,800 tonnes by 2027 |

|

French Climate and Resilience Law 2021, France |

Reduction of N2O emissions by 15% of 2015 levels and NH3 emissions by 13% of 2005 levels by 2030 |

|

National Emissions Ceilings Regulations 2018, UK |

Reduction commitments for NH3 of 16% by 2030 relative to 2005 levels |

|

Wales, UK |

Reduction of agricultural GHG emissions by 28% by 2030 compared to 1990 |

International action

The UN Environment Program (UNEP) previously considered ‘an aspirational goal for a 20% relative improvement in full-chain NUE by 2020’ (Sutton et al., 2014). However, Sutton et al., (2021) found that this could lead to an unfair distribution of effort whereby everyone had to increase their NUE by a relative amount. If this was the case a farm currently operating with high efficiency, e.g., 60% NUE, would have to increase by 12% to reach this 20% target. Whereas a farm operating with low efficiency e.g., 10% NUE, would have to increase by 2% to reach the same 20% target.

To overcome this unfair distribution, a target to halve N waste was seen as a more equitable approach as less waste means less action is needed. For example, to reduce N waste by 50%, a farm with higher N waste e.g., 100t N/yr would have to reduce by 50 t N/yr and a farm with less N waste e.g., 10 t N/yr would have to reduce by 5t N/yr. Therefore, the largest effort needed is placed on farms with higher N waste (low NUE) as opposed to farms already operating with high efficiency (high NUE).

Alongside the support from the UNEP and the technical support of the International Nitrogen Management System (INMS), the Colombo Declaration represents the first-time that governments are collaborating on an ambitious, quantitative, and global N management target by seeking to cut N waste by 50% across the world.

Outside Europe

New Zealand’s Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 includes a target to reduce N2O emissions to net zero by 2050. Canada (which has set a target to reduce fertiliser emissions by 30% by 2030) applies a region-specific approach due to the vast expanse of the country having variable meteorological conditions.

The European Union

The Nitrates Directive (1991) aims to protect water quality across Europe by preventing nitrate losses from agricultural sources through the promotion of good farming practices and includes limitations on N application from manures. Nitrate Vulnerable Zones (NVZs) are areas where the water bodies, such as lakes or rivers, are considered ‘at risk’ because there they have more than 50 mg/l of NO3– or are eutrophic. Farmers in these areas must comply with rules set out in the Member States’s action programmes to reduce the risk and the Managing Authorities need to report on NO3– concentrations in ground and surface waters. The Directive does not focus on N emissions other than NO3–. While the Nitrates Directive has driven a reduction in nutrient application over the last 30 years, targets have failed to improve NUE in many areas with reported high levels of N surplus (N remaining beyond plant and soil requirements) found in the Netherlands, Belgium, north-west Germany, Luxembourg and Brittany in France.

The National Emissions reduction Commitment (NEC) Directive (2016) is the current primary European regulation requiring actions to improve air quality and sets targets for reduction in the emissions of key air pollutants. This is important in an agricultural context due to the inclusion of setting reduction targets for NH3. Target reductions are specific to each Member State and vary significantly with the target NH3 reduction for 2030 ranging from 1% for Estonia and 32% for Hungary.

The European Green Deal (2019) is the EU’s holistic plan to achieve net zero GHG emissions across the EU, while improving biodiversity and human health. The Farm to Fork strategy (2020) includes targets to reduce the use of N fertilisers and losses of N to the environment to support improvements in air and water quality and to reduce emissions of GHGs. The strategy sets a target to reduce nutrient losses by at least 50%, while ensuring that there is no deterioration in soil fertility. The European Commission expect this to reduce the use of fertilisers by at least 20% by 2030.

Considering the European wide scope of the directives and strategies to reduce N pollution, our study findings were surprising in that examples of nationwide NUE targets are limited. Whilst no country has a standalone NUE target, some countries such as Ireland and Denmark have incorporated NUE as an ‘action’ as part of a programme or another target (e.g., GHG target).

The Danish example relates to the historic, 1980 ‘Good Agricultural Practice Program’ where increasing NUE was part of a suite of actions to reduce N use. This program was unsuccessful in limiting emission effects and as such ‘harmony rules’ were introduced, which, along with other measures, increased the Danish national NUE to an average of 40%. The Danish harmony rules prescribe the minimum area that a livestock farm must have for spreading livestock manure from their livestock production, thus limiting N inputs to land from livestock manure (Sommer and Knudsen., 2021).

Ireland’s Climate Action Plan 2021 put forward a suite of actions to deliver their GHG target that includes N. Action 359 details the implementation of ‘a suite of measures to improve NUE’. Teagasc, who is leading this action, sees that there is room for improvement across Irish dairy farms with an industry target of 35% NUE “set for farmers to achieve in the coming years” – an improvement of 10% from the current NUE of 25%.

Also in 2021, Denmark introduced the ‘Green transition of Danish agriculture’ which has set an agricultural target to reduce GHG emissions by 55-60% by 2030, including a reduction of N emissions by 10,800 tonnes by 2027. The specific impacts on the aquatic environment are further covered through their Action Plan on the Aquatic Environment III which has targets to reduce N leaching.

France, through the French Climate and Resilience Law 2021, have set targets for reduction of N2O emissions by 15% of 2015 levels and NH3 emissions by 13% of 2005 levels by 2030 (Hawley., 2022). This law includes measures to reduce the use of mineral N fertilisers.

The United Kingdom

In the UK, there are N relevant targets at both UK-wide and devolved levels. Nitrate vulnerable zones (NVZ), designated as part of the Nitrates Directive (1991), aim to reduce nitrate water pollution by encouraging good farming practice. Areas where the concentration of nitrate in water exceed 50 mg/l in ground and/or surface waters have been designated as NVZs. There are at least 70 NVZs in England and Wales, covering 55% of agricultural land in England and 2.3% of Wales. Five areas of Scotland (Lower Nithsdale, Lothian and Borders, Strathmore and Fife (including Finavon), Moray, Aberdeenshire / Banff and Buchan, and Stranraer Lowlands) have been designated as NVZs.

The National Emissions Ceilings Regulations (NECR) (2018) commits the UK to reduce NH3 of 8% by 2020 and 16% by 2030, both relative to 2005 levels. The 2020 target was not met, but there has been a 12% reduction since 2005[2]. The NECR also contains reduction targets for nitrogen oxides (NOx), of 55% by 2020 (which was met) and 73% by 2030 but agriculture is a less important source.

Wales have set a target of reducing its total agriculture specific GHG emissions by 28% by 2030 compared to 1990. There are currently no UK-wide agriculture specific GHG emissions reduction targets, however, there is a UK-wide target of net zero by 2050, and agriculture will play an important role in achieving this target. For example, Defra has implemented new regulations on the use of urea fertilisers from 2023, which means that only urease-inhibitor treated or protected urea fertilisers may be used throughout the year, while untreated/unprotected urea fertilisers may only to be used from 15th January to 31st March each year. This regulation is expected to deliver an 11kt reduction in ammonia emissions by 2024/2025.

Why set a NUE target in Scotland?

It is important to consider the size and balance of the different Scottish agricultural sectors to understand the NUE potential of each sector. This section provides detail on the different forms of N found in Scottish agriculture, their impact on flows of N and how they can be targeted to improve NUE. A list of mitigation measures to improve NUE can be found in Appendix E and the impacts of these measures on NUE in Scotland are discussed in section 6.2.

The most recent Scottish GHG Statistics (2021) states that 2MtCO2e of N2O was emitted from the agricultural sector, which is a quarter of Scotland’s agriculture sector’s total GHG emissions and 2/3rds of total N2O emissions. N2O is emitted from soils after the application of N-fertilisers and manures (Brown, 2021). In addition, 90% of Scotland’s total NH3 emissions are attributed to the agricultural sector. Tackling the emissions of these pollutants will directly contribute to the following Scottish Government policies and ambitions:

- The Nitrates Directive is the basis of Scotland’s five NVZs under the Nitrate Vulnerable Zones (Scotland) Regulations 2008[3],

- the Scottish Government’s Biodiversity strategy to 2045: tackling the nature emergency, has the ambition of “restored and regenerated biodiversity across the country by 2045”,

- the Scottish Government’s Cleaner Air for Scotland 2 delivery plan

- the Pollution Prevention and Control (Scotland) Regulations 2012,

- target 7 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework to ‘reduce excess nutrients lost to the environment by at least half including through more efficient nutrient cycling and use’. The UK is a signatory to this framework and Scotland signed the associated Edinburgh Declaration,

- National GHG targets set by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019

- the CCPu sets out an ambition for the Scottish agriculture sector to reduce emissions by 31% from 2019 levels by 2032, and a commitment to “work with the agriculture and science sectors regarding the feasibility and development of a SMART target for reducing Scotland’s emissions from nitrogen (N) fertiliser.”

Understanding N flows in Scotland

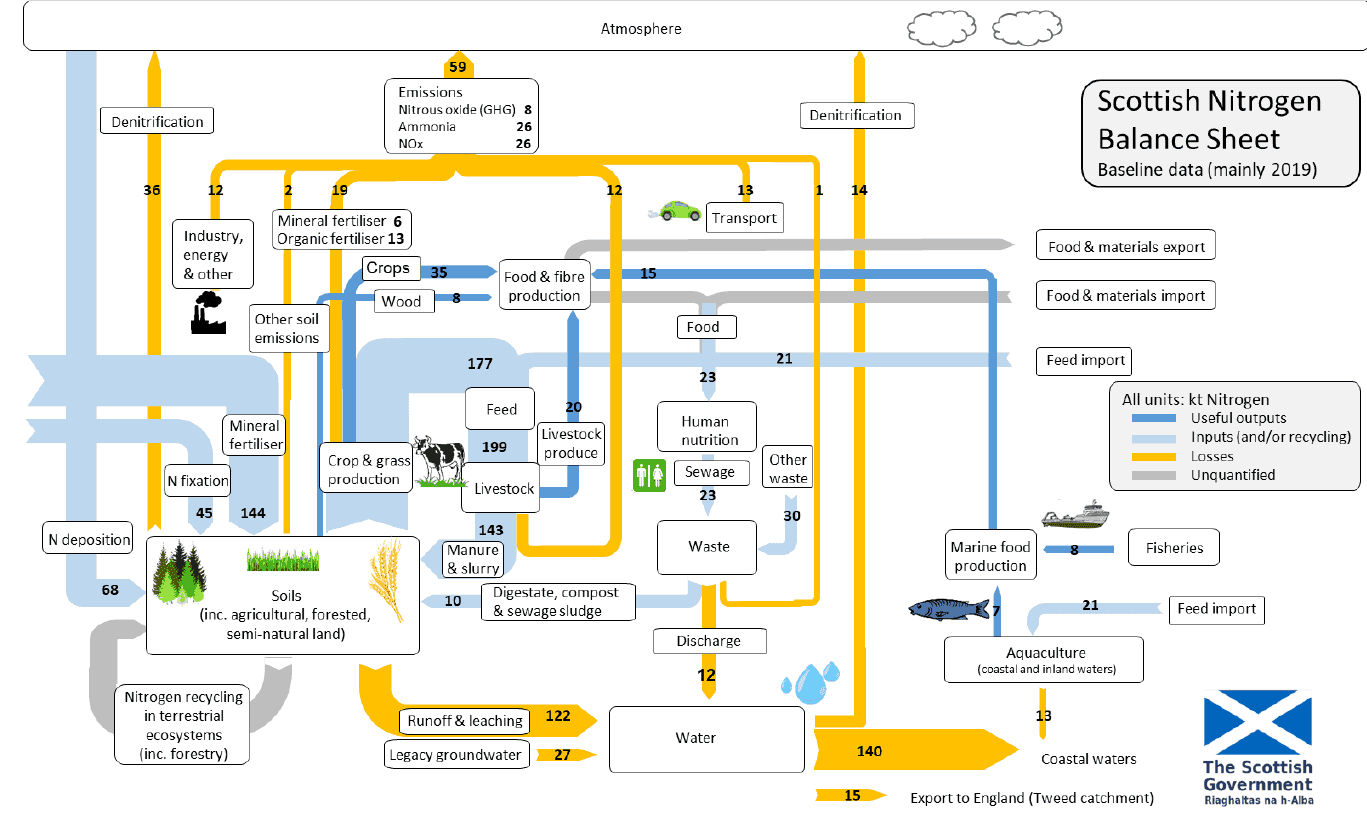

In recognition of the potential for reducing N to reduce total GHG emissions, the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 set requirements for Scottish Ministers to create a Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet (SNBS) from 2022 (Figure 3). The N flows in the SNBS combine data across all sectors of the economy and environment forming an evidence base to support the optimal use of N across all economic sectors to achieve optimal economic and environmental outcomes. While the SNBS was published in 2022, the data within it relates to 2019. Scotland is currently the only country to have planned to regularly update a cross-economy and cross-environment N balance sheet.

Figure 3. Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet (baseline data (mainly 2019)). Source: 3. Results from the initial version of the Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet – Establishing a Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

The annual SNBS report to the Scottish Parliament presents an assessment of:

- progress towards implementing proposals and policies relevant to improving NUE in Scotland,

- any future opportunities for improving NUE in Scotland, and

- how NUE is expected to contribute to the achievement of future emissions reduction targets (as per section 98 of the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019)

In 2022, the SNBS report published NUE values for agriculture as a whole sector (27%) with more granular figures of 65% for crop production NUE and 10% for livestock feed conversion. This valuable baseline shows NUE’s potential for improvement which can reduce emissions from all forms of N to support improvements in air and water quality with positive implications to both human (Pozzer et al., 2017) and biodiversity health (Houlton et al., 2019). While the SNBS is a valuable baseline for improving N management it is important to note the specificities of its set-up particularly on how different quantities of N are attributed to different sectors and how this relates to what happens in practice (more detail on this can be found in Section 6.5).

Research has found that the global arable NUE is 35%. When we do not consider all the variables which impact NUE and NUE target setting, as discussed in sections 3.2 and 4.2, the Scottish arable NUE of 65% appears to compare well to international data, however, some EU countries have arable NUEs of up to 77%, showing there may be room for improvement. The 2022 SNBS report states total N losses from agriculture to the environment amount to 30.2 kt N/yr as air pollutants (NH3, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and N2O) and 104 kt N/yr from runoff and leaching from agricultural soils.

Targeting different forms of N

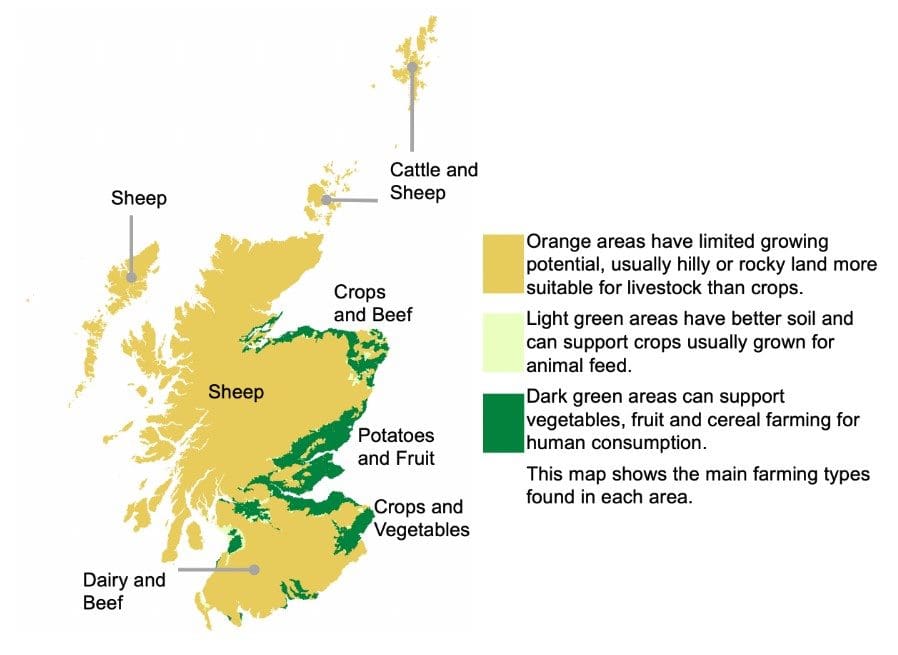

The different N inputs and outputs of Scottish agriculture are described below (also see Figure 3). Most of Scotland’s 5.64 million ha of agricultural area is best suited to livestock farming with a significant proportion occupied by cattle and sheep in Less Favoured Areas (LFAs) (55% or 3,159,137 ha) followed by crops and grass (1,885,701 ha), shown in Figure 4. Non-LFA cattle and sheep (107,712 ha) and specialist dairy (106,935 ha) are large sources of N in manure. More intensive sectors such as pigs and poultry do not have a direct correlation between NUE and land area, however they are significant sources of manures and contribute to N inputs. These areas are used to track N flows from the SNBS against sectors of particular potential in section 4.4.2. Note that forestry and aquaculture are out of scope of this project but will have impacts on Scottish N flows.

NUE varies between different Scottish farm types as the biological utilisation of N influences the potential NUE. The SNBS shows that livestock farms currently have a lower NUE (10%) than arable farms (65%). This is partly due to the relative inefficiency in the conversion of ingested N in feed converting to stable N within livestock products (milk and meat).

N Inputs

Fertiliser as the N input

The SNBS details that one of the largest flows of N in Scotland (143.8 kt N/y) is the use of inorganic fertiliser on arable crops and grass, with 62.1kt of this inorganic N applied to crops per year and 81.7kt going to grass [4]. The British Survey of Fertiliser practice states that in 2022, 63 kg N/ha were applied on average to all crops and grass in Scotland.

There is little information on N use in Scottish horticulture and permanent crops. Nonetheless, N fertiliser recommendations for vegetables, minority arable crops, bulbs, soft fruit and rhubarb crops exist. The high value of many of these crops and the technological advances taking place in this sector facilitate a higher degree of precision in management (e.g., GPS use for N application, leaf N monitoring, fertiliser application within irrigation water etc), which allows a better understanding of N flows in these systems. Targeted N applications could lead to reductions in inputs and waste thereby improving overall NUE for these crops. However, to date there are no recommended NUE levels for these specialist crops, thus more research is needed to understand the impact of reduced N applications on crop health and yield.

The evidence relating to the N requirements for the majority of crop and grass areas in Scotland is well described within the technical notes, and recommendations for NUE targets could build upon the evidence supporting these recommendations. Like specialist crops, improvements in fertiliser practices and technology can support improvements in N applications which will help matching of N inputs to crop requirements with greater precision and thus improves NUE.

Livestock Feed intake as the N input

The optimum levels for dietary crude protein are often exceeded to ensure that N intake does not limit either growth or welfare. This excess of N supply in the diet results in surplus N being excreted through manure and urine leading to N losses. Cattle cannot efficiently convert dietary N (efficiency ranging between 22-33%) and therefore, on average, 75% of consumed N is wasted, mainly through excretion. Matching N supply in feed with livestock requirements is part of ‘precision livestock feeding’ which can increase farm profitability, reduce emission intensity of methane (Rooke et al., 2016) and reduce N intake and excretion. Reductions to NH3 and N2O emissions from livestock sources due to precision feeding vary widely. However, studies have found that a reduction in crude protein of 2% leads to a 24% reduction in NH3 emissions in broilers, and a 1% crude protein reduction in pig feed results in a 10% reduction in NH3 emissions (Santonja, 2017).

The SNBS found one of the largest N flows is N excreted by livestock (142.9 kt N/y). The control of N levels added to soil from livestock directly impacts the input part of the livestock NUE calculation. A NUE target aimed at the livestock sector may be most impactful as it currently has the lowest NUE (10%) whilst also covering the largest amount of agricultural land (combined total of 3.3 million ha) meaning even a small, targeted improvement in NUE for livestock could have a significant impact on the overall N budget.

N Outputs

Ammonia as the output

NH3 from agricultural sources produces particulate matter which can impact human health, causing diseases such as cardiovascular and respiratory disease. In addition, NH3 emissions can result in the long-range transport of N compounds and this N deposition can cause acidification and eutrophication. Scottish agriculture accounts for 90% of total NH3 emissions, which have decreased by 12% over the last 30 years. NH3 is tied specifically to the (housed) livestock sector, with most emissions (35% of NH3 emissions) coming from cattle manure management. Livestock housing and storage of manure is responsible for 10.5kt N/y in the form of NH3 emissions, therefore improvements targeted at this sector would directly improve NUE. Examples of mitigation measures which can be introduced to lower the NH3 emissions in this sector are detailed in Table 3 under section 6.2.1 and include slurry store covers and slurry acidification.

Use of urea based inorganic fertilisers can lead to significant losses of NH3. High temperatures and winds at the time of fertiliser application or very dry conditions can lead to high levels of NH3 volatilisation (the conversion of NH4+ to NH3 gas) with a significant proportion of the N being lost and unavailable to the plants. A useful mitigation measure is the use of urease inhibitors with urea fertilisers to reduce these emissions.

Nitrate leaching as the output

Excessive leaching of N from agricultural activity can lead to water pollution and eutrophication which can then result in the loss of aquatic biodiversity and GHG emissions. The SNBS shows N run-off and leaching from crops and arable land as 45.5 kt N/yr and from grass as 58.5 kt N/yr. This N is lost as NO3–, which is readily mobile in soil water or runoff. Any N that is lost from the soil is no longer available to plants thereby lowering the potential NUE and increasing agricultural pollution.

According to Adaptation Scotland, Scotland is predicted to experience an increase in rainfall, with intense, heavy rainfall events increasing in both winter and summer. This has the potential to increase N leaching as soil moisture controls both crop N uptake and N leaching (McKay Fletcher et al., 2022). In addition, Scotland’s topography affects the rate of run-off as steep slopes promote surface run-off. When considering Scotland’s topography and the predicted change in rainfall, the potential for leaching will increase and continue to negatively affect water quality. Those areas currently most at risk are classified as NVZs.

Nitrous oxide emissions as the output

N2O is a GHG that accumulates in the atmosphere and directly contributes to climate change. The SNBS shows 5.9kt N2O per year is emitted from the agriculture sector. This includes 0.9kt from livestock (including manure management), 3.8kt from soil management (including mineral fertiliser use), and 1.2kt of indirect emissions (from N deposition and NO3– leaching). N2O is produced in the process of denitrification, where denitrifying bacteria under conditions where oxygen is limited (for example waterlogged soils) use the NO3– available in soil. By using the NO3–in soil, these bacteria reduce the NO3– available by plants potentially negatively impacting yield. In conditions where NO3– is available in excess denitrification can reduce NO3– losses through leaching. However, since N2O is produced in the process, negative impacts on climate are the result. Total elimination of N2O emissions from agriculture is not possible; however, some mitigation is possible through improvements in soil conditions and avoidance of N fertiliser application under wet conditions (Munch and Velthof, 2007).

Crop and livestock outputs

Crop and livestock products are the useful outputs of N from agriculture. In Scotland these account for 54.5kt N per year. This value includes livestock products, including meat, milk, eggs, and wool, and harvested crops used for food for human consumption (but excludes crops for animal feed or fodder). Useful crop outputs also include seed, feed and straw, but these are retained in the agricultural system and so are not final outputs.

Cereals, explicitly for alcohol production, accounts for the largest useful output flow in Scotland at 20.5kt N, followed by livestock products at 19.6kt N and crop product for human consumption at 12.2kt N (all values per year).

Optimising the quantity of N recovered in these outputs i.e. the N is taken up by the plant or animal and used to increase growth, relative to the quantity of inputs (feed and fertiliser) is key to reducing N waste and improving NUE. Managing the quantity of N application to meet crop and livestock requirements alongside the soil conditions will improve the overall NUE.

Viability of a SMART Target for NUE in Scotland

This section looks at the viability of setting a NUE target for Scotland and provides a summary of the risks and benefits of setting a Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound (SMART) NUE target in Scotland and presents how a range of influences can support or hinder the achievement of a NUE target. Information on N targets in other countries was considered and analysed for their applicability to Scotland. Since no other country has a standalone NUE target, we had to rely on information on other N targets for our analysis and transfer these finding to a NUE target for Scotland. The methodology can be found in Appendix F.

Analysis Tools

SWOT analysis

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) of setting N-related targets were analysed based on the information gathered on N targets in other countries. We also included analysis of GHG and climate related targets where relevant to increase the body of information. This information was then used to assess applicability of setting a NUE target for Scottish agriculture with the limitation that the analysis was based on N, GHG and climate related, rather than NUE specific targets. The SWOT analysis shows a range of influences which can support or hinder the achievement of a NUE target. The full SWOT analysis can be found in Appendix F.

PESTLE analysis

Setting NUE and other N targets are subject to a range of enablers and barriers. Therefore, a political, economic, social, technical, legal, and environmental (PESTLE) analysis was undertaken to assess the feasibility of setting a NUE target for Scottish agriculture, again, with the limitation that the analysis was based on N, GHG and climate related rather than NUE specific targets. The PESTLE assessment took place following the SWOT analysis to ensure the findings from the SWOT were assessed and, if relevant, included into the PESTLE categories. The full PESTLE analysis can be found in Appendix F.

Discussion

Supporting a SMART NUE target

The SNBS is reviewed and updated annually and provides a source of data for measuring and monitoring the changes in NUE and thus the progression of a NUE target. In addition, all mitigation measures identified in section 6.2 and analysed for their effect on Scottish agriculture NUE are captured by the SNBS. The use of the SNBS enables a measurable target. This was identified as a strength and technical enabler in the analysis of setting a NUE target.

Another strength and technical enabler identified through the analysis includes the mitigation measures required to achieve a NUE target. N-related mitigation measures are well understood, and many are relatively low cost and already practiced in Scottish agriculture (e.g., use of catch and cover crops) which makes reduction in N losses achievable. Furthermore, measures continue to be developed through additional research e.g. in Canada to understand the emission reduction potential, costs and benefits of different measures at farm level.

Section 6.4 recommends years 2030, 2040 and 2045 as deadlines which would ensure a NUE target is time-bound. These years align with other emission targets set in Scottish Government which may affect agriculture and therefore complement a new, potential NUE target. Including three timed steps into a binding target would also help measure the progression of the NUE target whilst also encouraging the delivery of high reductions.

A NUE target would be relevant in meeting statutory emission reduction targets. Introducing a NUE target would lower N-related emissions and would therefore contribute to other emissions reduction targets, for example the CCPu which aims to reduce agricultural GHG emissions by 31% from 2019 levels by 2032. Similarly, a NUE target would be relevant to several other environmental issues as the implementation and success of a NUE target would have multiple benefits for example, improvements to water quality, air quality (Sutton et al., 2014), human health and biodiversity (Houlton et al., 2019).

The SWOT and PESTLE analysis identified influences needed to support a specific and achievable NUE target by detailing opportunities which could assist with the implementation of such a target. Regulatory instruments include BAT/mitigation measures and fertiliser use limits, economic instruments include taxes and subsidies, and communicative instruments include extension services and awareness (Oenema et al., 2011).

Other positive influences include an increase in farm profitability following the implementation of mitigation measures such as precision livestock feeding and matching N supply to demand) which was found as a strength and economic enabler through the analysis. Moreover, through the introduction of a NUE target, there would be an opportunity to involve advisors and consultants which may also lead to the implementation of better advice and practice regarding N use in Scottish agriculture.

Hindering a SMART NUE target

All analysis was based on N targets rather than NUE targets due to the lack of any NUE specific targets in other countries. Therefore, clear evidence on NUE targets is lacking and the analysis of a NUE target for Scotland is based on assumptions through transferring information from N-related targets to NUE.

To achieve any potential NUE targets a range of new techniques, technologies and systems would be required. These are referred to as mitigation measures. There is already a good body of evidence and supporting examples of the implementation of mitigations. These have been identified as a strength and enabler as some examples such as variable rate N application (precision farming) can save farmers money on inputs by only purchasing and applying N as needed. Others, however, require significant capital expenditure with upfront investment of time and money required to implement some of the mitigation measures (for example, low emission slurry application equipment). This has also been identified as a weakness and economic barrier which may be experienced by Scottish farmers. This could directly impact upon the achievability of a NUE target. Similarly, several barriers to uptake of mitigation measures were identified as a threat through the SWOT analysis. Barriers include lack of awareness and knowledge of why and how to improve N use, and farmer’s personal beliefs, both of which may lead to Scottish farm managers finding it difficult to quantify the benefits to their business and understand the relevance of a NUE target. These barriers would generally hinder the achievability of a NUE target.

In trying to make a NUE target relevant in terms of meeting statutory emission reduction targets, there is a risk when reducing N-related emissions, through mitigation measures, that pollution-swapping takes place. An example of this is the decrease in NH3 emissions and an increase in N2O emissions (due to nitrification/denitrification processes) when using slurry injection (a type of low emission slurry application) compared to surface application. Pollution-swapping as an unintended consequence of some mitigation measures was identified as a threat and environmental barrier in introducing a NUE target.

Farmers’ perception of a national NUE target for Scotland may limit target achievability. Scottish farmers may not understand how their practices impact NUE and how introducing on-farm mitigation measures may impact on a general NUE target for Scottish agriculture. For example, questions may arise on how many and at what frequency the relevant mitigation measures need to be introduced by each farmer to achieve this overarching target. To overcome this, some farmers may respond more positively to several more specific targets, for example a reduction of fertiliser input (by a certain amount and by a certain date). Alternatively, ensuring a NUE target is accompanied with very specific and relevant action points on how this NUE target would be achieved so that farmers have a clear understanding on what is expected of them and their farming system to contribute to a national NUE target.

The time taken to create and process the appropriate legislation for a NUE target can be uncertain and longwinded. This process has the potential to directly impact the time-bound element of a SMART NUE target.

In the Netherlands, an ambitious target led to civil unrest where more than 10,000 Dutch farmers have been protesting following government plans to reduce N emissions. Similarly, when targets or limits are seen to be a barrier to economic performance, implementation of new regulation can become challenging, as is seen in the case of revising the approach towards Nutrient Neutrality in England. The use of a SMART target is therefore critical to avoid the implementation of a policy which is neither appropriate nor achievable.

In the main, these examples relate to current exceedances of regulations under the Habitats or Nitrates directives, follow a long period of previous actions and constraints on the farming sector and relate to farming systems which are very different to those present within Scotland. In addition, these regulations are not focused on NUE but rather on the achievement of environmental targets and so do not consider the productive potential of the sector. Notwithstanding these differences, these risks do indicate the importance of well formulated targets, based on sound scientific understanding and with a clear plan for consultation and implementation on their achievement and delivery.

The political and legal barriers identified include the potential for pushback on mitigation measures which are seen to reduce productive output and a concern that Scottish farmers may not comply with regulatory requirements. This could directly impact upon the achievability of a NUE target.

Development of a NUE target for Scotland

Assessment using the Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet

The SNBS has been used as a baseline to assess how practices that influence N pools or flows may impact the agricultural NUE value. This dataset contains values for key sectors, pools (stores of N within parts of the N cycle e.g. in manure, in soils or in livestock/crops), and flows of N (movement of N into different pools as the N form changes or is taken up by plant or animals). These flows include inputs to the system (e.g. fertilisers, animal feed), useful outputs (e.g. meat, cereals), and waste (e.g. NO3– leaching, NH3 emissions). Each of these flows have a value in kt N/yr assigned. The NUE is improved by either increasing the output flow values or reducing input and waste flow values. This can be modelled by estimating the impact of a mitigation measure (e.g. improved nutrient planning or reduced protein livestock feed) and applying these values to the relevant N flow in the SNBS (for improved nutrient planning this would be reduced inputs of fertiliser and reduced N emissions to atmosphere). This produces estimates for N flows that can then be summarised in NUE calculations as currently setup in the SNBS, resulting in estimates of improved NUE values (see Appendix E for a detailed methodology and all assumptions).

Mitigation measures

The effect of mitigation measures on Scottish agriculture’s NUE

This section presents and discusses the effects of 18 different mitigation measures on the current NUE of Scottish agriculture.

The table below presents modelled estimates for the NUE of Scottish agriculture, by individual measure and at each future projected target year. The values reflect implementing the relevant measure individually and compared to the current whole-agriculture NUE of 27.2% (i.e. preventing soil compaction may improve total NUE by 0.1% by 2030). The results show the impact for the relevant measure in isolation and do not reflect any combination effects for interactions with other measures. Further detail on the assumptions and methodology can be found in Appendix E. The 2030, 2040 and 2045 scenarios are based on minimal change, continuing recent trends of recent changes in uptake, but including greater increases where there is precedent to, e.g. low emissions spreading techniques all increasing to 95% by 2030 as this will be required under the New General Binding Rules on Silage and Slurry. However, the 2045 Ambitious scenario is based on a transformational change across the sector where there is greater effort to improve NUE to meet a legally binding target. Therefore, the improved NUE in the 2045 and 2045 (Ambitious) scenarios may be viewed as the range where a target may be set, where the lower bound of the range (2045 scenario) is more achievable, while the higher bound (2045 (Ambitious) scenario) would require more effort across stakeholders to be achieved but is a better value.

Table 3 List of mitigation measures and their effect on Scottish agriculture NUE (%) compared to the current whole agriculture NUE of 27.2%. The two 2045 scenarios can be viewed as an ideal range for NUE; where the lower bound (2045 scenario) reflects changes to agriculture planned to come in (current and upcoming legislation, expert judgement on technological developments etc.); while the upper bound (2045 ambitious scenario) reflects the possibility for a greater push from industry and government to improve NUE (financial incentives, increased awareness of N management, etc.).

|

Measure |

2030 |

2040 |

2045 |

2045 (Ambitious) |

|

Avoid excess N |

31.23% (-3.02%) |

31.90% (-3.48%) |

31.90% (-3.48%) |

33/41% (-5.59%) |

|

VRNT |

27.66% (-0.43%) |

27.96% (-0.72%) |

28.41% (-1.16%) |

30.40% (-3.02%) |

|

Urease Inhibitors |

27.57% (-0.35%) |

28.08% (-0.86%) |

28.35% (-1.12%) |

28.70% (-1.47%) |

|

Improving nutrition |

27.26% (-0.03%) |

27.30% (-0.07%) |

28.27% (-1.04%) |

28.26% (-1.03%) |

|

Novel crops |

27.44% (-0.22%) |

27.52% (-0.29%) |

27.77% (-0.55%) |

27.81% (-0.58%) |

|

Low emission spreading |

27.62% (-0.39%) |

27.62% (-0.39%) |

27.62% (-0.39%) |

27.62% (-0.39%) |

|

Rapid incorporation |

27.26% (-0.09%) |

27.31% (-0.09%) |

27.34% (-0.11%) |

27.47% (-0.24%) |

|

Low emission housing |

27.24% (-0.02%) |

27.27% (-0.04%) |

27.28% (-0.06%) |

27.43% (-0.20%) |

|

Improving livestock health |

27.64% (-0.42%) |

28.02% (-0.80%) |

27.32% (-0.09%) |

27.43% (-0.20%) |

|

Slurry cover |

27.25% (-0.02%) |

27.28% (-0.05%) |

27.03% (-0.07%) |

27.33% (-0.10%) |

|

Optimal soil pH |

27.25% (-0.02%) |

27.29% (-0.06%) |

27.30% (-0.07%) |

27.30% (-0.07%) |

|

Nitrification inhibitor |

27.23% (-0.01%) |

27.24% (-0.02%) |

27.25% (-0.02%) |

27.25% (-0.03%) |

|

Improving GI + genomic tools |

27.23% (0.00%) |

27.23% (-0.01%) |

27.23% (-0.01%) |

27.25% (-0.03%) |

|

Slurry acidification |

27.23% (0.00%) |

27.24% (-0.01%) |

27.24% (-0.01%) |

27.25% (-0.02%) |

|

Preventing soil compaction |

27.23% (-0.01%) |

27.24% (-0.01%) |

27.24% (-0.02%) |

27.24% (-0.02%) |

|

Use of catch and cover crops |

27.27% (-0.05%) |

27.34% (-0.11%) |

27.37% (-0.15%) |

27.38% (-0.18%) |

|

Legume-grass mixtures |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

Grain legumes in crop rotations |

– |

– |

– |

– |

There are potential interactions/overlaps between several of these measures. Where this occurs, measures cannot be applied on the same unit (area of land/head of livestock) at the same time as they are mutually exclusive. We have avoided double counting these effects by resolving the total maximum applicability across overlapping measures i.e. the combination of measures cannot exceed the total land available to apply the measure to.

The key outcomes are:

- The measures with the greatest potential improvement on NUE are nitrification inhibitors, improving livestock nutrition, and improving livestock health.

- Nitrification inhibitors are more effective at improving NUE than urease inhibitors as they can be applied to a greater proportion of fertiliser products used in Scotland (both NO3– and urea-based products, while urease inhibitor can only be applied to urea-based products).

- Improving livestock nutrition will improve NUE by reducing the overall quantity of N being fed to livestock while maintaining liveweight yield.

Measures that are based on the use of legume crops were not included in the modelling of the new NUE values, as the reduced requirement for inorganic fertiliser input will be offset by increased biological fixation of N from the atmosphere. Both flows are included in the N input values when calculating NUE in the SNBS. Therefore, the total N inputs levels will stay constant, as will the outputs, and so there is no impact on NUE. However, there are benefits of legume crops beyond an improvement to NUE, which should be considered, namely the effects of reduced requirement for inorganic fertiliser inputs (lower GHG emissions), improved soil health and soil function, and reduced costs. This is likely to be economically beneficial to the farmer, as soil health benefits the local ecosystem and improves resilience, reduced fertiliser use avoids emissions from manufacture and transportation of inorganic fertiliser; all of which are benefits from moving to a circular economy.

Potential N savings through implementation

The table below summarises the potential savings of N inputs of mineral fertiliser in both absolute values in kt N yr-1, and relative to the quantity in the current SNBS as a %. The values presented here include fertiliser use savings due to legume-based measures (legume-grass mixtures, and legumes in crop rotations). The effect of these measures is not included in calculations of NUE due to the assumption that the saved fertiliser N application will be replaced by increased N deposition from the atmosphere.

Table 4 Absolute values of N inputs of mineral fertiliser saved in kt N per year and as % of the quantity in the current SNBS when all modelled measures are included. The two 2045 scenarios can be viewed as an ideal range for NUE; where the lower bound (2045 scenario) reflects changes to agriculture planned to come in (current and upcoming legislation, expert judgement on technological developments etc.); while the upper bound (2045 ambitious scenario) reflects the possibility for a greater push from industry and government to improve NUE (financial incentives, increased awareness of N management, etc.).

|

Year |

2021 (kt N yr-1) |

Savings (kt N yr-1) |

Savings (%) |

Savings (kt CO2e yr-1) |

|

2030 |

143.78 |

36.36 |

25.29 |

160.09 |

|

2040 |

143.78 |

44.16 |

32.12 |

213.41 |

|

2045 |

143.78 |

53.14 |

37.96 |

248.56 |

|

2045 (Ambitious) |

143.78 |

78.22 |

-54.40 |

361.15 |

Recommended criteria for target(s) setting for Scotland

When modelling the NUE improvements and the establishment of potential targets, the key criteria for consideration are listed below.

Mitigation measures

The measures/farming practices that have been included for modelling are the result of literature searches and expert judgement. Measures that impact N flows in agricultural systems, and the relevant data, were extracted from literature. These were then reviewed to ensure applicability to Scotland, and any other measures that were identified by experts as being important were also researched.

Current uptake

The current uptake provides a basis from which to estimate what future uptake may be possible and the likely rate of additional implementation. It also supports the calculation of a baseline or counterfactual against which change can be measured. These values come from the same sources which have provided the NUE impact values (see Appendix E for detail on current uptake for each measure).

Applicability

The applicability values refer to the portion of a SNBS N flow that a measure’s impact value can apply to. Expected future uptake

The expected future uptake values are estimates based on expert judgment and consultation within the project team. The values for each measure can be found in Appendix E and are additional to the current uptake levels. These values increase over time to reflect increasing commitment to NUE improvements. The two 2045 scenarios can be viewed as an ideal range for NUE; where the lower bound (2045 scenario) reflects changes to agriculture planned to come in (current and upcoming legislation, expert judgement on technological developments etc.); while the upper bound (2045 ambitious scenario) reflects the possibility for a greater push from industry and government to improve NUE (financial incentives, increased awareness of N management, etc.). The expected future uptake ranges from 1% to 100% depending on the measure and scenario. For example, soil compaction was only expected to increase by 2% even in the 2045 (Ambitious) scenario as it was assumed that where soil compaction is occurring most farmers will already be taking steps to improve it. While low emission spreading techniques increased to 95% by 2030 to reflect the New General Binding Rules on Silage and Slurry. A full example is provided in Appendix G.

Timescales

We modelled potential NUE targets for Scottish agriculture for 2030, 2040, and 2045. These were chosen to align with Scotland’s Climate Change Act 2019 with a target date of 2045 for reaching net zero GHG emissions.

One NUE target for Scottish agriculture or per sector?

Currently, the arable sector is more N efficient than the livestock sector (65% and 10% respectively). This difference is due to inherent qualities of livestock systems with animals unable to process N as protein as efficiently as plants uptake N. The current NUE should, however, be seen as a baseline, and the scale of improvements from this should be the focus rather than an absolute target applicable to all sectors and systems. The majority of measures included in the modelling of NUE improvements target the soil N pools (arable and grass land), therefore separate targets for each sector are advisable.

Analysis of recommendations

The table below presents the estimated NUE values in 2030, 2040, and 2045 based on increased uptake of on-farm measures. As well as an additional value for the year 2045 where increased ambition has been included in the projected uptake values.

Table 5. Potentially achievable NUE estimates in 2030, 2040 and 2054 based on increased uptake of on-farm measures. The two 2045 scenarios can be viewed as an ideal range for NUE; where the lower bound (2045 scenario) reflects changes to agriculture planned to come in (current and upcoming legislation, expert judgement on technological developments etc.); while the upper bound (2045 ambitious scenario) reflects the possibility for a greater push from industry and government to improve NUE (financial incentives, increased awareness of N management, etc.).

|

Potentially achievable NUE estimates (%) | |||||

|

2021 (Current) |

2030 |

2040 |

2045 |

2045 (Ambitious) | |

|

Whole agriculture |

27.2 |

33.7 |

35.7 |

38.2 |

40.9 |

The NUE values that are modelled in this study are based on the selected measures, and the achievement of these NUE targets rely on their implementation. Other agricultural practices may impact N flows, as will changes in the size of agricultural sectors.

Similarly, the NUE values that have been calculated are based on the levels of implementation that have been included in the modelling. Achieving these targets in practice will require supporting instruments to encourage the uptake of these measures. As stated in Section 6.2.1, the NUE values in the above table for 2030 and 2040 reflect assumptions on uptake based on minimal change and not a transformational change to the sector (such as the setting of a target). Therefore, these values should not be viewed as potential targets for these years, but as indicators of the feasibility of improvements to NUE in Scottish agriculture.

Sector specific NUE values are not currently feasible due to the calculation set-up in the current SNBS (which flows are considered as inputs/outputs for arable and livestock), and the assumption made in the modelling that production will not increase and only inputs will decrease. This set-up leads to results that make it seem that the arable sector is mining N, which is not the case. Improvements to the set-up of calculations to overcome this barrier are outlined in Section 6.5 below.

Guidance for future implementation

In the current version of the SNBS, the NUE calculations do not align directly with what happens in practice in the different agricultural sectors because there are overlaps and movements of N flows between the different agricultural sectors that are not easily viewed in isolation. For example, in practice, improvements to NUE due to implementation of manure management measures will largely be implemented by the livestock sector. However, given the current set-up of the calculations in the SNBS, N flows related to manure management may not be attributed to the livestock sector NUE values as they will reduce emissions from spreading of organic matter to soils, which would be reported in the arable sector calculation. This would make it more difficult to use the SNBS to set and measure sectoral targets. Therefore, accurately monitoring the changes in NUE and attributing these changes to the correct sector would be important if considering sectoral targets. Accurately representing N flows in the SNBS to the relevant sector may be difficult, due to, for example, data availability, different ways data is collected across mitigation measures and sectors and difficulties in correctly separating overlaps and movements of N flows between the different agricultural sectors, however, could significantly help the feasibility of achieving and monitoring NUE targets.

When reflecting the potential impacts of mitigation measures on the values in the SNBS, certain hurdles resulting from the disaggregation of flows make it more difficult and possibly less accurate. More details of these hurdles, and how they were overcome, can be found in Appendix E, but a key example here is the use of slurry acidification on livestock slurry. In the SNBS there is one flow of N from manure management to atmosphere which includes all manure storage types and all livestock types. However, the implementation potential and mitigation impact potential will vary between storage and livestock types. This required an assumption to be made on the breakdown of this manure management N flow so that the appropriate uptake levels and impact values can be applied to the correct portion of the total N value (in this instance the Scottish Agricultural Census was used). This can be considered a sound approach to reflect the mitigation measures in the current SNBS, however going forward, to improve the ease and accuracy with which targets can be projected and improvements can be measured, a more granular breakdown on the N flows in the agricultural sector in the SNBS are required.

Conclusions

A NUE target for Scotland

The rationale behind setting a NUE target for Scotland is to reduce the impacts of N wastages to the environment to lower GHG emissions and improve water and air quality. NUE values can be used as indicators for N resource use efficiency and as markers for improvement. Scotland is in the unique position to use and regularly update a cross-economy and cross-environment N Balance Sheet (SNBS). The SNBS provides a valuable baseline in the current performance of Scottish agriculture and provides a tool to tackle all forms of N pollution.

However, setting a NUE target is not without challenges and nowhere in the world has yet set a NUE target. NUE values are impacted by various factors (soil type, climate, crop type, livestock type, etc). Whilst research shows that the ideal range for NUE is between 50-90%, it is crucial to understand the different forms of N inputs and outputs and to allocate these correctly to the different farming sectors.

As no other country has yet set a standalone NUE target, we had to solely rely on other N-related targets for our evidence base. Our analysis of the viability of setting a NUE target for Scotland is therefore based on assumptions through transferring information from N-related targets to NUE.

The SWOT and PESTLE analysis carried out in this study highlighted several factors which can influence the success of a SMART NUE target for Scottish agriculture. Importantly, the use of the SNBS would make the target measurable and the fact that many N-related mitigation measures are well understood and already practiced in Scottish agriculture would make the target achievable. However, some mitigation measures require significant capital expenditure, such as slurry management equipment, or increased ongoing investment, such as nitrification inhibitors, or a change in focus, such as better-balanced protein in livestock feed. These changes would need support from the farming sector. Using NVZ regulations as an example, a small study conducted in 2016 (Macgregor and Warren 2016) showed that some farmers regarded the NVZ regulations as “burdensome and costly”. To avoid similar responses to setting NUE targets, farmers would need to be able to quantify the benefits to their business and understand the relevance of a NUE target for climate and the environment. It is therefore important to accompany NUE targets with specific actions points expected by farming businesses. Providing funding to farmers to help implement mitigation measures and share knowledge on the impact to their businesses, the climate, water quality, air quality and biodiversity is likely to aid faster and easier uptake of these measures.

Looking at initiatives worldwide, we know that N use can be targeted in many different forms (fertiliser use, livestock diet, reduction of N waste, reduction of emission of air pollutants, etc.) and alongside the proven mitigation measures discussed above, it is clear that improvements to NUE are achievable.

Modelling NUE improvements using the SNBS

In this study, the SNBS has been used to model NUE improvements by estimating the impact of a mitigation measure and applying these values to the relevant N flow in the SNBS. It is important to note that these results show the impact for the relevant measure in isolation so do not reflect any combination effects for interactions with other measures. In the arable sector, the mitigation measures with the greatest potential to improve NUE are the use of variable rate N application (precision farming) and the use of nitrification inhibitors potentially increasing NUE to 28.8% and 29.7%, respectively, by 2045. In the livestock sector, improving nutrition and improving livestock health (NUE of 31.7% and 29.4% respectively by 2045) have the greatest potential. Overall, the modelling suggests that total NUE of Scottish agriculture could be increased to 38.2-40.9% by 2045, depending on the level of implementation of mitigation measures.

Sector specific NUE values are not presently feasible due to the calculation set-up in the SNBS and the assumptions that production will remain stable, with only inputs decreasing. In the current version of the SNBS, the NUE calculations do not align directly with what happens in practice in the different agricultural sectors because there are overlaps and movements of N flows between the different agricultural sectors that are not easily viewed in isolation and not necessarily attributed to the correct sector. For example, mitigation measures around manure management will, in practice, be mainly implemented by the livestock sector but will, in the current calculations, be attributed to the arable sector because they are linked to reduced emissions from spreading of organic matter to soils.

The feasibility of a NUE target for Scotland

This research indicates that a NUE target for Scotland is not currently feasible. We see potential for such a target in the future but recommend to first consider several points for improvement.

- The SNBS. Improvements to the calculations and attributions of flows of N to the different measures and sectors are required. The modelling for this report depends on assumptions and figures from another CXC report (Eory, et al., 2023). We recommend updating this data with real on farm data to better inform assumptions that follow from it.

- The sectors. Currently, the arable sector is more N efficient than the livestock sector (65% and 10% respectively). Sector specific targets would be helpful due to differences in current NUE, N inputs and N wastages but this is presently not possible due to the current limitations in the SNBS.

- The mitigation measures. More data on the impacts of mitigation measures under Scottish conditions would increase the accuracy of modelling achievable aims. Since NUE values are both indicators of resource efficiency and markers for improvement, it is possible to focus on mitigation measures with the most potential to improve NUE values.

- Farmers. It is highly important to ensure that targets and measures are clearly understandable and achievable for farmers to create support from the farming sector.

A potential target figure?

If a NUE target was set, this could be in line with the modelled potential NUE estimates of 38.2-40.9% by 2045, depending on mitigation measure implementation. To achieve greater improvement, a combined push from industry and government (financial incentives, increased awareness of N management, etc.) is required. This additional push is reflected in our ‘Ambitious scenario’.

However, based on our research findings, the barriers identified to implementing an achievable and successful NUE target and the need for farmer and industry support to achieve changes in practices and expectations, we conclude that focusing on reducing N waste is likely to have more success than NUE targets as a policy option. Experience from the United Nations Environment Assembly’s discussions on N and the Green Deal’s Farm to Fork targets, has shown more success in including the reduction of N pollution in policy when focusing on N waste over NUE targets. NUE can instead be used as a technical tool to mark improvements, with the SNBS key to setting a baseline and providing a visualisation of the combined impacts of implemented mitigations measures over time. We therefore recommend setting a target for N waste.

An alternative – a N waste target?

Opportunities for setting a N waste reduction target include:

- It is an easier concept to communicate to the farming community and other N producing sectors.

- It gives the opportunity to value any N as a resource until it is lost as waste, creating options for greater collaboration between the arable, horticulture and livestock sectors. Any potential bias towards a sector will be avoided.

- Each individual farmer and land manager would be encouraged to reduce N waste for the economic and environmentally beneficial outcomes. The positive messages around a N waste target would be likely to create support from the farming sector.

- Achievements towards an N waste target would achieve reductions in national NUE thereby achieving the same objectives without the current issues around NUE targets.

Following the Colombo Declaration of 50% reduction of N waste and the Green Deal target of reducing nutrient waste by 2030, a reduction of 50% of N waste in Scottish agriculture would align with other examples. However, we recommend further research to determine a realistic N waste target for Scotland.

Research gaps for setting a N waste target

In the SNBS, N flows would need to be properly assigned to N waste and N re-use. Legumes would need to be included in the SNBS because N waste is likely to be lower than N input. A SMART target analysis for N waste would be beneficial to set a challenging and realistic target. It would be helpful to closer investigate the relationship between N waste and NUE targets if a NUE target is the long-term aim.

References

Antille, D. L., Moody, P. W. 2021. Nitrogen use efficiency calculators for the Australian cotton, grain, sugar, dairy and horticulture industries. Environmental and sustainability indicators, ELSEVIER.

Adaptation Scotland 2021 Climate Projections for Scotland Summary. https://www.adaptationscotland.org.uk/application/files/1316/3956/5418/LOW_RES_4656_Climate_Projections_report_SINGLE_PAGE_DEC21.pdf

Barnes, A., Bevan, K., Moxey, A., Grierson, S. and Toma, L., 2022. Greenhouse gas emissions from Scottish farming: an exploratory analysis of the Scottish Farm Business Survey and Agrecalc. Scotland’s Rural College.

Brown, P., Cardenas, L., Choudrie, S., Del Vento, S., Karagianni, E., MacCarthy, J., Mullen, J., Passant, N., Richmond, B., Smith, H., Thistlethwaite, G., Thomson, A., Turtle, L. & Wakeling, D. (2021) UK Greenhouse Gas Inventory, 1990 to 2019. Ricardo Energy & Environment, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, London quoted in Climate Exchange, 2023, Scenarios for emissions reduction targets in Scottish agriculture.

Duncombe, J. (2021). Index suggests that half of nitrogen applied to crops is lost, Eos, 102. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO162300.

Emmerling, C., Krein, A. and Junk, J., 2020. Meta-analysis of strategies to reduce NH3 emissions from slurries in European agriculture and consequences for greenhouse gas emissions. Agronomy, 10(11), p.1633. https://www.mdpi.com/867332

Eory, V., Topp, K., Rees, B., Jones, S., Waxenberg, K., Barnes, A., Smith, P., MacLeod, M. and Wall, E., 2023. A scenario-based approach to emissions reduction targets in Scottish agriculture. Scotland’s Rural College. http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/3048

Eory, V., MacLeod, M., Topp, C.F.E., Rees, R.M., Webb, J., McVittie, A., Wall, E., Borthwick, F., Watson, C.A., Waterhouse, A. and Wiltshire, J., 2015. Review and update the UK agriculture MACC to assess the abatement potential for the 5th carbon budget period and to 2050: Final report submitted for the project contract “Provision of services to review and update the UK agriculture MACC and to assess abatement potential for the 5th carbon budget period and to 2050”.

EU Nitrogen Expert Panel (2015) Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) – an indicator for the utilization of nitrogen in agriculture and food systems. Wageningen University, Alterra, PO Box 47, NL-6700 Wageningen, Netherlands.

Germán Giner Santonja, Konstantinos Georgitzikis, Bianca Maria Scalet, Paolo Montobbio, Serge Roudier, Luis Delgado Sancho; Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Intensive Rearing of Poultry or Pigs; EUR 28674 EN; doi:10.2760/020485

Hawley, J., 2022. A comprehensive approach to Nitrogen in the UK.