Social housing decarbonisation case studies: Summary report

Research completed: February 2024

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/4549

Executive summary

There is a need to decarbonise our heating sources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Switching from fossil fuel-based technology, such as gas and oil, to low-carbon electricity is a significant step in this process.

To achieve Scotland’s emissions reduction targets, the number of zero direct emissions heating systems (ZDEH) installed, such as heat pumps, needs to increase.

Social landlords have begun taking steps to improve the energy efficiency of the homes they rent out and to meet standards set by the Scottish Government, such as the second milestone of the Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing (EESSH2). In recent years, their work has included a rising number of ZDEH projects.

Aims

This research has developed a series of case studies to support social landlords in their delivery of future ZDEH projects. The learnings from this report and the associated case studies seek to encourage social landlords to deliver more decarbonisation projects, and support the delivery of Scottish Government’s net zero targets.

Findings

The findings may not be fully representative as they only relate to eight case studies.

The majority of the case studies installed air source heat pumps. Most social landlords were confident in writing funding applications.

- Engaging with tenants throughout the project is important to delivery, and seeing the new heating system in person can increase tenant confidence.

- Delivering at least one building as a pilot helps identify and address any challenges. This engagement needs to continue after the installation as new heating systems may not be intuitive to use and require behaviour change; supporting tenants with this is important in achieving tenant satisfaction.

- Key considerations to project planning were overlooked by some landlords, resulting in challenges, delays and/or unforeseen costs. These included: unexpected costs in relation to gas meter removals, changes to the built environment required for planning permission and upgrades to the electricity grid required for solar panels.

- All of the case studies aimed to increase affordability for residents. However, the energy crisis has made impact on affordability difficult to assess. Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) ratings improved across all projects, with the majority of properties achieving an EPC B or C rating post-installation[1]. Overall, there was limited data to quantify the impact of the new heating systems, but landlords reported that anecdotally tenants feel positive about their new heating system.

Lessons for future social housing heating projects

Some lessons for social landlords:

- Tenant engagement: Consider a mixed-method approach to engage and support a range of residents, such as face-to-face events, ongoing support and opportunities to see and use the technology in-situ.

- Impact evaluation: This should be planned from the outset of the project to truly understand the impact of the project on tenants, its success in achieving its aims and how it might be improved for next time. The methodology should provide a before and after picture, and include temperature and humidity assessments, energy consumption data and EPC data.

- Multiple buildings: In projects involving large or multiple buildings, delivering at least one building as a pilot helps identify and address any challenges. Rolling the installations out in one building helps to reduce disruption and focus tenant support.

- Project management and costs: If you plan to procure a project manager, involving them from the outset means that they can support with application writing. It should be noted that there may be a cost to this, which should be taken into account. Consider aspects such as planning permission requirements, meter changes and electricity grid upgrades at an early stage to avoid unexpected costs.

Glossary / Abbreviations table

|

ABS |

Area Based Schemes |

|

EESSH |

Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing. When the EESSH was introduced in March 2014 it set a first milestone for social landlords to meet for social rented homes by 31 December 2020. A second milestone (EESSH2) was confirmed in June 2019, for social rented houses to meet by December 2032. |

|

EPC |

Energy Performance Certificate |

|

Housing Revenue Account |

A ring-fenced account which is separate from the council’s General Fund. The account is for income and expenditure relating to the management and maintenance of the council’s housing stock |

|

LCITP |

Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme |

|

SHNZHF |

Social Housing Net Zero Heat Fund |

|

ZDEH |

Zero Direct Emissions Heating |

Introduction

Importance of decarbonisation

Greenhouse gas emissions from Scotland’s homes account for 13% of the total emissions in Scotland. The Heat in Buildings Strategy sets out the Scottish Government’s commitments both to decarbonise heating and to remove poor energy efficiency as a driver of fuel poverty.

In Scotland, 23% of domestic dwellings are social housing. The social housing sector has shown strong leadership on improving fabric energy efficiency, with the aim of supporting tenants to reduce their energy bills and contributing to carbon savings. However, to achieve net zero targets, the installation of zero direct emissions heating systems (ZDEH) such as heat pumps, is also needed.

Research aims

The research reviewed case studies to assist landlords in their planning for meeting the standard that will replace EESSH2.[2] The case studies show how various measures, including a change in the heating system, can improve the energy efficiency of their dwellings.

The learnings identified in this report and the associated case studies seek to:

- Encourage social landlords across Scotland to deliver more decarbonisation projects in their housing stock;

- Improve delivery of domestic decarbonisation projects, especially in the social housing sector, by building on existing learnings and solutions;

- Support the delivery of the Scottish Government’s net zero targets.

Method overview

Local Authorities and Housing Associations were approached in equal measure to provide case studies. However, in the research time available, only one Local Authority was able to commit. Furthermore, while many council-led decarbonisation projects exist many of them were out of scope of this research, either due to their focus on new build homes or because the projects were not yet complete. Additionally, some councils no longer have social housing.

Therefore, the higher ratio of Housing Associations to Local Authorities in this report should not be taken as evidence of a greater or lesser willingness to participate in decarbonisation projects from parts of the sector. Lessons are relevant across all social landlords.

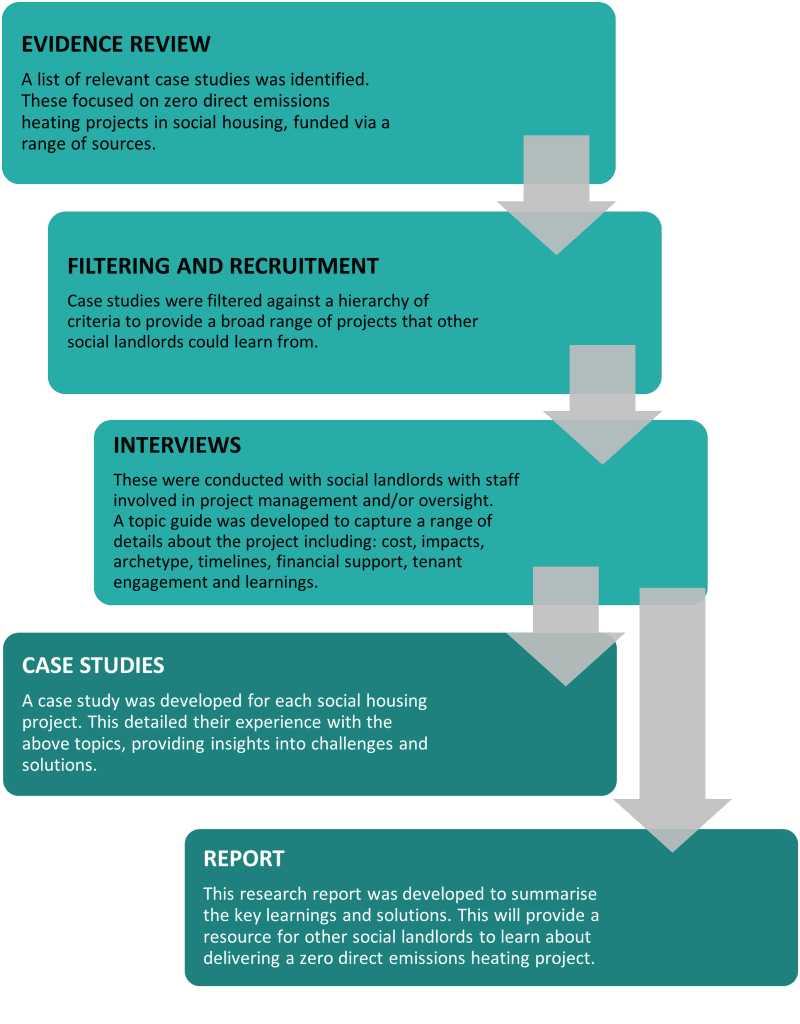

The methodology is summaries in figure 1.

Overview of case studies

Eight case studies were selected from a range of social housing projects across Scotland:

- Angus Housing Association ‘Kirkbank Renewable Heat Project’ delivered 32 air source heat pumps in a mix of private and social rented housing to replace inefficient storage heaters. Solar photovoltaic (PV) panels and electricity storage batteries were also installed. The project took place between 2018 and 2022.

- Grampian Housing Association ‘Mackenzie Gardens’ Zero Emission Heating Project’ installed three commercial air source heat pumps, creating a heat network servicing 17 flats and three terraced houses. The project took place between 2021 and 2023.

- Hebridean Housing Partnership ‘Hebridean Heat Pumps Project’ installed air source heat pumps in a wide range of archetypes across 102 of their social rented properties. For three householders, this replaced solid fuel heat sources. The project took place between 2022 and 2023.

- Maryhill Housing Association ‘North-west Glasgow Replacement Heating Project’ installed 266 air source heat pumps into 11 seven-storey housing blocks. Their aim was to contribute towards their net zero targets whilst offering tenants a more affordable alternative to the existing electric storage heaters. The project took place between 2018 and 2021.

- North Lanarkshire Council ‘Lorne Gardens Air Source Heat Pumps Project’ installed air source heat pumps in 20 properties in a retirement housing complex. This also included cavity wall insulation for some of the properties. The project took place in 2021.

- Osprey Housing ‘Moray and Aberdeenshire Heat Pumps 2021 Project’ installed air source heat pumps in 61 properties, accounting for 20% of their off-gas housing stock. This was to provide a cost-effective alternative to the electric storage heating that had been used in the properties previously. The project took place between 2020 and 2022.

- Queens Cross Housing Association ‘Regeneration of Cedar Multistorey Flats in Woodside Project’ delivered a number of retrofit upgrades to a newly acquired tower block. This included an electric wet central heating system as their new form of zero direct emissions heating. Options appraisals began in 2012, with project delivery taking place between 2016 and 2023.

- Rural Stirling Housing Association ‘Old Kirk Loan and Craigmore View Heat Replacement Programme’ replaced older storage heaters with air source heat pumps in 40 properties, alongside installing solar PV panels and electricity storage batteries. This was to ensure that the properties met the requirements of EESSH2. The project took place between 2021 and 2022.

About this report

This report provides an overview of the above case studies. It gives social landlords a summary of the key challenges and successes experienced and draws lessons for future projects. The report should not be viewed as a comprehensive piece of research into the experiences of social landlords in delivering zero direct emissions heating projects, as it does not include sufficient numbers of projects to draw any wider conclusions.

Context

Scottish decarbonisation targets and policies

Heat in Buildings Bill and Strategy

The Scottish Government is currently consulting on a Heat in Buildings Bill with proposals on legislation covering energy efficiency standards and heating system requirements. This bill follows on from the 2019 Heat in Buildings Strategy, which outlines how Scotland will reduce greenhouse gas emissions from buildings and remove poor energy performance as a driver of fuel poverty. Since homes and buildings account for a significant portion of Scotland’s greenhouse gas emissions, the Bill is important in achieving Scotland’s statutory emissions target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. The Bill will provide a regulatory framework that will drive the development of heat networks, the adoption of zero emission heating systems, and improved standards of energy efficiency.

The Heat in Buildings Strategy sets out the changes required to ensure Scotland’s buildings no longer contribute to climate change. As part of the support package to deliver the strategy, the Scottish Government has committed to invest £1.8 billion in heat and energy efficiency over the lifetime of the parliament. This includes the £200 million allocated to projects through the Social Housing Net Zero Heat Fund.

Energy efficiency standards for social housing

As part of the Heat in Buildings Strategy, the Scottish Government has established targets to improve the energy efficiency of social housing. The purpose of the standard is to encourage landlords to improve the energy efficiency of social housing in Scotland.

EESSH was originally introduced in 2014 and set an initial target for social landlords to meet by the end of 2020. This meant that no eligible social property in Scotland was to be lower than EPC band C or D by the end of 2020.

EESSH2 was established in 2019. It specified that all social housing must meet EPC band B, or be as energy efficient as practicably possible, by the end of December 2032. It also stated that no social housing below EPC band D should be re-let from December 2025, subject to temporary specified exemptions. At the time of writing, EESSH2 has been under review to realign the standard with net zero targets, and the 2032 milestone has been put on hold.

In November 2023, the Scottish Government launched a consultation on a new Social Housing Net Zero Standard, which will replace EESSH2. The proposed new standard includes a minimum fabric efficiency rating and would introduce a requirement to replace polluting heating systems with clean alternatives by 2045. Energy efficiency target ranges and interim target years have been proposed but are yet to be decided.

EPC reform

Improving energy efficiency is an important aspect of the Scottish Government’s decarbonisation and fuel poverty strategies, and EPCs are the most widely used tool for assessing the energy efficiency of properties. A number of issues with the current EPC methodology have been raised in recent years. These include that the current main metric is a cost efficiency rating which does not adequately incentivise the building and heating system improvements necessary to meet net zero targets.[3]

As set out in the Heat in Buildings Strategy, the Scottish Government is progressing work on the reform of EPCs.[4] A consultation on this topic closed in October 2023. The reform proposes to introduce new metrics that, among other things, separate out fabric efficiency and cost, and carbon emissions. The Government is also exploring options for the inclusion of energy use data to make EPCs more accurate and consistent (research by Changeworks, forthcoming). The reform will impact how buildings are assessed to ensure that they comply with Scottish regulations.

Retrofit programmes for social housing

This is a list of current and closed retrofit programmes for social housing and how the funds operate. Most of the case studies accessed one of these funding streams.

Social Housing Net Zero Heat Fund

The Social Housing Net Zero Heat Fund (SHNZHF) is an ongoing Scottish Government programme that supports the decarbonisation of social housing in Scotland. Funding is given to social landlords to install energy efficient zero emissions heating systems in their housing stock. The fund has £200 million available up to 2026.[5]

Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme (Closed 2020)

The Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme (LCITP) was a partnership between the Scottish Government and a range of other enterprise organisations and experts. The aim was to support Scotland’s transition to a low-carbon economy. This involved providing financial support to assist the development and delivery of low-carbon projects. The focus was to assist projects that would secure public and private finance to demonstrate innovative low carbon technology in Scotland. As part of this, financial support was made available to some social landlords delivering zero direct emissions heating projects.[6]

Area Based Schemes

The Area Based Schemes (ABS)[7] is a programme developed by the Scottish Government. It provides grant funding to local authorities to develop and deliver energy efficiency programmes, including measures such as insulation, solar PV and batteries, and air source heat pumps: “This funding is blended with owner’s contributions and funding from Registered Social Landlords who may choose to insulate their homes at the same time”.[8]

Scotland’s Heat Network Fund

Launched in 2022, Scotland’s Heat Network Fund makes £300 million available to applicants from the public and private sector to support the roll-out of large-scale heat networks in Scotland.[9] The Heat Network Support Unit (HNSU)[10] supports pre-capital stages of heat network development.

Other financing options/models

See section 11.2 for other previous funding that shaped the retrofit project landscape over the past 10 years.

Case study aims and motivations

Scotland’s buildings need to decarbonise. The case studies examined in this research demonstrate a range of approaches to how this can be achieved. They also display the many different motivations that underpin the choice to take action on specific buildings.

One of the key priorities present throughout all of the case studies was increasing affordability for residents. In six of the eight case studies, the previous heating system was electric storage heaters, which are known to be both expensive in their operation and can make it difficult to maintain a comfortable temperature. Complaints from residents about high energy costs motivated several of the social landlords to install new heating systems. Two of the landlords had carried out surveys which found that many tenants were unhappy with their existing heating systems.

One housing association noted that in moving from storage heaters, which are controlled room by room, to a central heating system would provide greater comfort for residents.

The decision to install air source heat pumps also related to regulatory requirements for housing associations. While both EESSH2 and EPCs are undergoing review and reform (see sections 4.1.2 and 4.1.3), many social landlords have begun the work needed to bring their housing stock to EPC band B.

For some, the presence of funding was a motivating factor which aligned with other priorities. As one social landlord expressed:

“We had access to funding, it was the right thing to do for the tenants and for the EESSH targets.”

Hebridean Housing Partnership, who have been installing heat pumps in their properties since 2011, described their main driver as “getting ahead of the curve” and making the most of the available funding to install as many heat pumps as possible.

Wider organisation-established goals related to net zero and decarbonisation also factored in, though generally not as highly as the other priorities. One Housing Association, whose project was the only case study that changed the heating systems from gas central heating, did so as part of their goal of being net zero, and they had a clear strategy:

“We wanted to get tenants on board with the idea of decarbonisation. We wanted it to be a positive experience that we could then sell to the rest of our tenants, because that’s the journey we’re on – [we have] committed to being net zero by 2035.”

Their priority was to demonstrate that switching to electric heating does not have to impact people financially, and thus set a positive example which would help deliver more projects in the future.

Overall, the social landlords expressed an awareness and concern for their tenants’ limited income, and some said that this is holding them back from switching on-gas properties to zero direct emissions heating systems.

Key findings: Project planning

Funding and project costs

Six of the eight social landlords we spoke to had received funding from the Social Housing Net Zero Heat Fund (SHNZHF) or the Low Carbon Infrastructure Transition Programme (LCITP). Two social landlords had not applied for Scottish Government funding. One of these was Queen’s Cross Housing Association, who had their project funded through a second stage stock transfer, and whose project began before Government funding became available in 2015. The other, North Lanarkshire Council, found there was no specific retrofit funding available for local authorities when they started the project in 2021, before the launch of the SHNZHF. Instead, their project was funded from their Housing Revenue Account.

Applications

Many found that the process of applying for funding was straightforward, and they were confident that they could do this themselves. Several social landlords found that a key to success was to demonstrate a robust tenant engagement strategy and to focus on the benefits for the householders. As one housing association representative said:

“I have found that Scottish Government are quite good at caring more about what the project is trying to achieve, than focusing too much on the language.”

To help develop their applications, one social landlord consulted with specialists to get figures for expected carbon savings. Another social landlord explained that they considered the application complex and found it useful to partner with a consultant. One social landlord, who used a consultant to write their proposal, has since found that some contractors are willing to include consultancy and application writing in the contract.

One social landlord found that the wait time to get funding confirmation was too long. Despite being ready to go ahead with installations in April, the funding was not confirmed until August of the same year. This caused delays in the timeline that had already been agreed with the contractor.

Internal staff costs

When speaking to the social landlords, we found that most did not consider internal staff costs as a part of the total project cost. When considering the full cost of retrofit, landlords may wish to consider the time and cost not directly related to installation of measures, such as applications, tenant engagement and support provided by their own staff. In the absence of this information, it makes it difficult to get a sense of the full cost of this work and how it varies across the projects.

Key findings

- Most social landlords felt confident about writing the funding applications.

- Some social landlords found it helpful to have a third party involved in writing the funding application or in calculating anticipated carbon savings.

- Staff costs related to tenant engagement were typically considered outside of the project costs and therefore their relative contribution was difficult to quantify.

Heating system considerations

6 domestic air source heat pumps | 1 commercial air source heat pump network | 1 electric wet central heating system |

Several factors influenced which Zero Direct Emissions Heating (ZDEH) system was chosen for the projects. These factors included:

- The type, condition, and location of the properties

- The available funding

- The priorities for the landlord

Air source heat pumps were the most common heating system choice across the case studies. In seven of the eight case studies, most properties had electric storage heating prior to the project installations.

Two projects included some properties using solid fuel, and one project switched the heating system away from gas central heating.

Comparing heat pumps and electric storage heaters

Both air source heat pumps and electric storage heaters fall under the category of Zero Direct Emissions Heating (ZDEH) systems since both run on electricity. Electricity is a less carbon intensive fuel type compared to other heating fuels (e.g. gas and oil). However, the efficiency of an air source heat pump is higher since it uses the latent heat energy in the air outside, resulting in more heat per unit of energy inputted.

Cost and affordability

Cost was a key factor across the case studies. Three of the social landlords considered ground source heat pumps, but the high cost of this solution led them to choose air source heat pumps instead. In one of these cases, there were also limitations related to the composition of the soil and the distance between the buildings, which made ground source heat pumps and district heating nonviable.

Air source heat pumps were preferred in most of the case studies as a more affordable and energy efficient heating solution. Though heat pumps are more expensive to install than electric storage heaters, they are cheaper to run for residents due to higher efficiency, resulting in higher EPC ratings (see Box 1). They are also an increasingly common and well-understood heating system and meet the SHNZHF criteria of having the potential to deliver a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

One project, delivered by Grampian Housing Association, installed three commercial air source heat pumps to supply 20 properties via a heat network. The key motivation was to increase efficiency and reduce heating costs for the residents. This was further achieved by also installing solar PV and battery storage.

One case study did not install a heat pump-based system. Air source heat pumps had been a desired option but there were not funds available for this after carrying out the prioritised fabric-first upgrades. Government funding was not available at the time to subsidise the measures, therefore electric wet central heating was chosen as a cheaper alternative.

Supply chain

Of the eight case studies, most of the social landlords did not highlight issues relating to the supply chain, however there were two exceptions to this. These landlords reported project delays due to material shortages and noted that many contractors at the time were struggling with supplies of heat pumps.

Maintenance and repairs

Two of the eight case studies referenced maintenance and repairs as a consideration in their choice of technology. They expressed concerns that eventual repairs of the air source heat pumps might be more expensive than the previous gas boilers and electric storage heaters. One social landlord explained that some of their concerns had been realised when some of their air source heat pumps began to develop faults. As a whole-house heating system, rather than a room heater as previously installed (with storage heaters), this was more expensive and challenging to deal with. In one case, a resident had to be relocated for three weeks while their heat pump was replaced.

The same landlord said that they also had worries regarding:

- Availability of organisations offering maintenance services due to the rurality of their area.

- Tenants’ understanding of air source heat pump controls, which it was felt could lead to a higher instance of faults and repairs required.

Planning permission

Two of the case studies experienced challenges that related to planning permissions. In the case of one project, some of the flats were required to have freestanding platforms built for the heat pumps in order to get planning permission. They felt that the platforms would negatively impact the aesthetics of the buildings, so these flats were removed from the project and other properties were included instead.

However, this was not possible for another social landlord for whom planning permission was a major obstacle to project delivery. Concerns had been raised over potential noise from the commercial air source heat pumps, which were close to other private properties. This delayed the project by a year and resulted in the housing association having to pay for sound consultants and the building of a sound box around the heat pump.

Key findings

- Air source heat pumps are the most common ZDEH choice among the case studies.

- High cost was the main reason why ground source heat pumps were not chosen for many of the projects.

- Planning permission needs to be taken into consideration from the outset, as this can result in changes or delays to projects.

Building types

The eight case studies included a wide range of properties built between 1950 and 2008, with the majority from the 1960s, 1990s, and early 2000s. Building types included multi-storey blocks, cottage flats (or four-in-a-blocks), bungalows, and terraced houses. In many cases, the buildings had already received fabric improvements such as external wall insulation, cavity wall insulation, and loft insulation, reducing heat loss enough to make air source heat pumps a viable option. In some cases, fabric improvements took place as part of the projects alongside ZDEH installations.

Most of the case studies encompassed buildings of a similar type and age, which meant that challenges associated with particular building types did not arise. The exception to this was the Hebridean 100 project, which included a wide variety of building types and ages. Despite this, Hebridean Housing Partnership did not report any challenges associated with the installations.

Maryhill Housing Association was able to install individual air source heat pumps in their seven-storey blocks by utilising the drying areas inside the buildings. A similar solution is unlikely to be available in other multi-storey blocks, but other alternatives exist, such as a shared air source heat pump system.[11]

Pilot projects

Multiple social landlords spoke positively about testing the proposed measures on one pilot building before carrying out installations in the rest of the buildings.

In one of the projects, air source heat pumps had already been installed in one block of flats before the landlord applied for funding for the remaining blocks. Another landlord, who did not take this approach, expressed that, in hindsight, it would have been beneficial, even if it had resulted in increased project costs and timelines. In particular, for projects with several large buildings, it was felt that piloting the installations in one building could help make the process smoother and less disruptive for the tenants.

Key findings

- ZDEH systems were installed across many different building types; none of the social landlords reported challenges associated with particular building archetypes.

- In projects involving large buildings, social landlords indicated that it is helpful to deliver at least one building as a pilot building, to better understand what challenges arise.

Impact evaluation

The aim of impact evaluation in the context of a retrofit project is to establish to what extent the aims of the project have been achieved, i.e. to provide evidence of the changes that have taken place as a result of the measures installed. The case studies show a wide variety of approaches to evaluating the impact of the projects. Overall, very little data is currently available either because it has not been collected or because collection is still ongoing. As a result, limited conclusions can be drawn on the outcomes of the projects. Despite this, the different approaches provide insights into the challenges and considerations relating to evaluation work. This section outlines the data that was collected. For a discussion on the findings of the evaluation work see section 8.1.

Data collection

Different aims and motivations (see section 5) affected what evaluation data was collected. EPCs were the form of data most commonly collected across the case studies. For the case studies that emphasised the importance of regulatory compliance, EPCs were considered the main focus of the evaluation work. Improvement in EPC ratings may reflect changes beyond the heating system, including the installation of other energy efficiency measures.

Pre- and post-install surveys were carried out by some of the social landlords, but in most cases, the response rates were low. This limits the ability to carry out a full impact evaluation.

Three projects have been collecting temperature and humidity data via sensors. This data is being collected over a period of at least 12 months to cover weather changes throughout the year, and the collection is still ongoing for two of the projects.

None of the case studies had energy bills or meter reading data that could be included in this research. This data can only be provided by the tenants, which makes it difficult to collect consistently across multiple properties. One social landlord navigated this challenge by collecting data during the annual heat pump servicing. This comprised heat pump and electricity meter readings as well as a satisfaction survey.

Usefulness of data

The social landlords had different perspectives on the importance and usefulness of collecting impact evaluation data. One social landlord explained that data collection was not a high priority on their project since they were confident that heat pumps were a viable option, having collected more evaluation data on previous projects. They highlighted the obvious benefits of heat pumps compared to other forms of electric heating. This landlord noted that future projects where properties are changing from gas central heating to heat pumps will likely require more impact evaluation work to ensure the change does not impact the residents negatively.

Another social landlord explained that collecting impact evaluation data was not a high priority for their limited resources and viewed this type of data as more beneficial to the Scottish Government than to the housing association and their tenants. On smaller projects, some of the social landlords felt that they knew what they needed to know from verbal feedback from their tenants. A majority of the social landlords in the case studies shared positive but anecdotal feedback from their tenants and considered a lack of complaints as a positive indicator.

Different factors drive these perspectives. Planning and delivering robust impact evaluation requires staff time, skills, knowledge, equipment, and funding. It also requires the foresight to plan in advance of the project to gather the necessary pre-installation data. This is particularly challenging since resources are limited for many social landlords. With time restrictions on meeting energy efficiency targets, EPCs become a key focus for many social landlords since it is how their performance is measured.

Key findings

- Social landlords prioritised impact evaluation to different degrees.

- EPCs are the most consistently available source of data across the case studies.

- Some social landlords carried out tenant satisfaction surveys, but overall response rates were low.

- Three case studies collected comprehensive data including from sensors, but for two projects data collection is not yet complete.

Key findings: Project delivery

Tenant engagement

The social landlords displayed care and experience in engaging with their tenants before and during the installation works. There were several different strategies taken, including:

- Carrying out pre-installation surveys

- Employing tenant liaison officers

- Demonstrating the heating system

- Hosting tenant engagement sessions

Tenant project approval

Some of the projects started from the point of tenants being unhappy with their existing heating system. Two of the social landlords surveyed their tenants and found concerns about heating and affordability.

Another landlord hired a consultant to carry out a phone survey with tenants, which focused on attitudes towards decarbonisation and climate change. The results showed that tenants were concerned about climate change and, as a result, were on board with the decarbonisation plans but were mainly concerned about the disruption of the work. The consultant also provided a liaison officer responsible for dialogues with the tenants.

“We didn’t want to just spring [the project] on them. They felt like they were being taken on that [decarbonisation] journey and that they were being listened to.” – Social landlord

A common strategy across the social landlords was to organise tenant engagement sessions, typically hosted in local community spaces. For most of the larger-scale projects, information was sent out in letters and on their websites, while smaller-scale projects were able to have one-to-one conversations with residents about the benefits and cost savings of the projects.

One of the larger projects involving several hundred properties found that they were unable to get in touch with some of the tenants, despite multiple attempts to make contact through letters and via housing officers. Conversely, another landlord found that since their tenants already knew they wanted a heat pump, few turned up to the consultation events.

Example flats

Several social landlords found that demonstrating the new heating system helped their tenants to feel more confident about the installation.

In one of the projects, the heat pump installer and manufacturer attended tenant engagement days, where they displayed the heat pumps and how they operated. The housing association found it helpful that information was provided by a third party, rather than from themselves as the landlord.

By chance, Grampian Housing Association had a void property that they decided to use as a space to demonstrate the installations that would be carried out. This helped tenants understand how the commercial air source heat pump network would work. Such heating system demonstrations were also helpful to residents who did not speak English as their first language.

Mixed tenure

The main focus of all eight case studies was on social housing tenants. Three of the projects also included buildings containing some privately owned properties. Of these, two included large building blocks.

In these case studies, private owners were hesitant to be involved due to the costs of installation. In one project, all five owner-occupiers declined to have air source heat pumps installed on the grounds of cost. In another project, external building works were completed for all properties, including the privately owned ones, but they declined any internal work, which would have been at their own expense.

Budget

Most of the case studies did not have a specific budget for tenant engagement, and the social landlords absorbed most of the tenant engagement costs as staff costs. As a result, the cost of tenant engagement was largely unknown in most instances.

There were two exceptions where external tenant liaison officers were used. Grampian Housing Association had this work carried out by an external consultant, and North Lanarkshire Council had a basic level of tenant engagement included it as part of the work carried out by the contractor who carried out the installations.

Key findings

- The social landlords had many different and often creative ways of engaging with tenants.

- Seeing the new heating system in person before installation can help residents feel more confident about the project.

- Some social landlords found it beneficial to have a third-party organisation involved in the dialogues with tenants or in demonstrating the heating system.

- Mixed-tenure projects remain a challenge. There were no examples of projects which resulted in the installation of ZDEH systems in privately owned properties.

Heating system installation

Location of heating system

The installation of air source heat pumps could present challenges related to the location of the heat pump and its pipework. Due to the layout of the properties, the multi-storey flats in Maryhill Housing Association ended up with significant pipework going across the walls of the properties, which some residents have been unhappy about. The social landlords felt that, on reflection, a better solution would have been to put the pipework under the floors, or at floor level so they are not in the line of sight.

There are also circumstances where the installer and the resident may have different opinions about the optimal location for the heating system. For example, the space selected by contractors might already be used by residents for storage or drying. Some social landlords navigated those situations by installing additional storage space or by paying the contractor the extra cost of placing the heating system elsewhere in the home.

In one of the projects, some of the new water tanks had to be put in a different location to the old ones due to size differences. In these cases, storage space was installed where the old water tank cupboard was located. Actions or adjustments such as these resulted in higher levels of satisfaction from the residents.

Redecoration

Three of the case studies mentioned the need for redecoration of the properties after the new heating system installations, and these cases provided some form of decoration allowance for tenants. These costs cannot be funded as part of grant schemes, and so would have been covered by the social landlords.

One of the social landlords reported that residents were unhappy with the impacts on the property after installation, such as lines where the carpet had been cut when new radiators had been fitted. The landlord gave an allowance for carpet replacements but not for other costs, under the reasoning that some things, such as wallpaper, had been installed at the tenant’s own risk.

Another of the social landlords who had provided a decoration allowance, said they would do this differently in future projects. They had found that the decoration allowance, which was given as cash, was sometimes spent on other things besides redecorating the property.

Unexpected costs

Several of the case studies experienced costs related to the project that they had not been able to plan for. These were different in each of the cases and are highlighted here to inform future projects.

Gas meter removal

Grampian Housing Association experienced a challenge around meters after installing commercial heat pumps. It turned out that the energy supplier charged a high cost for the removal of the gas meters. This was important because without the removal, standing charges were building up for the tenants. The housing association found that this cost could not be covered by the funding. Since removal is charged per meter, this led to a significant extra cost. Grampian Housing Association was the only case study that previously had gas heating and therefore was the only case to encounter this issue.

Grid infrastructure

In one rural property, the social landlord encountered a challenge around connecting the solar PV and battery storage to the electricity grid. The Distribution Network Operator sought a significant financial contribution to improve the infrastructure of the local electricity network to enable the connection. The issue of who will pay this cost has not yet been resolved.

Planning permission

Grampian Housing Association experienced a significant additional cost to install an acoustic enclosure around their commercial air source heat pumps to address the planners’ concerns about potential noise levels. Since they did not expect this cost at the start of the project, it was not covered by the grant funding. This issue also caused significant project delays.

Key findings

Examples of areas that may incur costs include:

- Gas meter removal

- Changes to the built environment required for planning permission

- Improvements to the electricity grid when installing solar PV

Key findings: Post project

Tenant support

Metering

It is often necessary to change the meter when a new heating system has been installed, and this proved to be a challenge in several of the case studies. Many of the properties had had electric storage heating with a dual rate electricity meter, which has lower rates at night when the heater is charging but higher costs during the day. Changing to an air source heat pump required having a single rate meter installed, to avoid disproportionately high costs for heating the home during the day.

Since energy accounts are a matter between householder and supplier, residents have to contact the supplier individually to request a meter change. This can be a slow and difficult process[12].

After their tenants had experienced these challenges, one social landlord contacted the company that supplied the majority of the properties to facilitate quicker installation of smart meters. In a different project, the contractor supported tenants in-person to speak with their supplier and ensure they got the correct meter. This was beneficial for both the residents and the housing association.

Using the new heating system

A common challenge with air source heat pumps was enabling residents to use them correctly and efficiently. Heat pumps work best when they maintain a constant temperature. This is different from gas boilers. which are typically operated for a few hours at a time, giving a shorter burst of heat, or storage heaters which heat up overnight and gradually release this heat during the day. One social landlord felt that they needed to shift residents’ mindsets around how and when to heat their homes.

Some of the social landlords made different heating controls available to support tenants in controlling their heating. In one project, this took the form of an app. The landlord explained that the app makes it is easier to adjust the temperature than the heat pump controls. This enables householders to set the temperature to be slightly lower when they are not in the house, and warmer when they are at home. The downside is that some demographics, especially older residents, may be unable to use the app, due to lack of access to a smartphone or the internet, or challenges with IT literacy.

In two of the case studies, the social landlords did not have dedicated resources to support their tenants in how to use the heat pumps efficiently. In one of the cases, a third party had been contracted to carry out tenant support for both meter change and use of the system, but for unclear reasons it did not go ahead. As a result, the social landlord is in the process of carrying out engagement, which is ongoing.

Key findings

- Meter changes can be more challenging and time consuming than expected, and difficult for some tenants to undertake without support.

- For many households, a new heating system may not be intuitive and require getting used to a very different way of heating the home.

- Ensuring ease of use of the new heating system for tenants is likely to result in higher levels of satisfaction.

Project results

As discussed in section 6.5, the available impact evaluation data is limited due to either not having been collected or collection not yet being complete. This section gives an overview of the high-level outcomes across the projects, where possible.

EPC ratings

All social landlords with data saw improvements in their properties’ EPC ratings as a result of the projects. Before the installations, all properties fell within band E, D, or C, with the majority in band D. After the measures had been installed, all properties achieved band C or B, with the exception of three solid wall houses whose EPC ratings decreased from band D to band E. It is unknown why this was the case and may have been the result of an assessment error.

The average improvement in SAP scores varied across projects depending on the building type, previous heating system, and whether other measures were installed. The most significant SAP score increase took place in Queens Cross Housing Association’s project. Before the project, a sample property[13] was in EPC band E, while all properties post-project achieved band C or B, depending on the number of exposed walls.

Affordability

All case studies faced the challenge that the heating system changes coincided with a period of significant energy price increases. As a result, many tenants have experienced higher energy costs despite their new heating system being cheaper to run per kWh. Since energy consumption data was not available for any of the projects, it is difficult to calculate the counterfactual (i.e. what would the energy costs have been if a new heating system had not been installed).

Tenant satisfaction

It has not been possible to draw definitive conclusions on the residents’ satisfaction with their new heating systems due to a lack of representative data. All social landlords reported that many of their tenants were happy with their new heating system. Most of the information was anecdotal, and several social landlords saw the lack of complaints as a success in itself.

“The thing with tenants is, if nothing’s going bad, you don’t hear from them.” – social landlord

Where tenant feedback was available, the negative comments primarily related to high energy costs or issues with understanding their heat pump and controlling the temperature. The positive comments related to feeling warmer and more comfortable, and finding the system easier to use. Some tenants felt positive about their new heating system despite high bills, as they took this to be a result of the wider energy price increases rather than a result of the new heating system.

Hebridean Housing Partnership was the only project where comprehensive tenant satisfaction data was available at the time of writing. Their survey, which was carried out as part of their annual heat pump service, reported a 95% satisfaction rate.

Key findings

- EPC ratings improved across all projects.

- The majority of properties achieved an EPC B or C rating after the installations.

- It has been difficult to assess to what degree the affordability has changed due to increased energy costs.

- Many social landlords anecdotally reported that their tenants feel positive about the heating system change, but there is limited data available to quantify this.

Conclusions

Social landlords in Scotland are in the process of improving their housing stock to meet future needs. Many are making use of Scottish Government funding, which has been made available for this purpose.

Most of the case studies included in this research have installed air source heat pumps. Compared to ground source heat pumps and heat networks, air source heat pumps have lower capital costs and require less involvement and responsibility from the housing provider, which makes them a more attractive choice for many social landlords. Some social landlords and tenants have experienced challenges around the operation of the air source heat pumps, including access to maintenance engineers.

The buildings in these case studies do not represent Scotland’s many older or ‘hard-to-treat’ buildings. Rather, many of the projects that have been completed so far involve buildings that were easier to upgrade, such as those that were ‘heat pump ready’ or only required cavity wall insulation.

The majority of the properties in this research switched from electric storage heating. The social landlords found that this necessitated a significant change in tenants’ heating patterns and behaviours, which was identified as a key challenge related to air source heat pumps. Doing this successfully requires a level of support for the tenants. The nature of heat pumps offers the benefit of more consistent temperatures. However, the constant use needed to efficiently achieve this, could be putting use of the heating system beyond the reach of those in fuel poverty. This is likely to prove more challenging when moving properties away from gas central heating.

Limited collection of impact evaluation data is a significant barrier to quantifying how the projects have impacted tenants. Without such data, the social landlords cannot determine whether the original aims of their project, such as increasing affordability and comfort, have been met. Some project data will become available in 2024. This research highlights that impact evaluation work is a long process, and the most useful data is collected consistently over a number of years.

Overall, the majority of the social landlords were satisfied with the outcomes of their projects and the installation process. Despite the lack of formal impact evaluation in some cases, many anecdotally described an encouraging response from their tenants and perceived the lack of complaints as a positive result. However, this absence of complaints does not necessarily guarantee satisfaction or that there would not be more to learn through seeking feedback directly.

Lessons for future social housing energy efficiency and heating projects

Lessons for social landlords:

- Tenant engagement: Consider a mixed-method approach to engage and support a range of residents, such as face-to-face events, ongoing support and opportunities to see and use the technology in-situ.

- Impact evaluation: This should be planned from the outset of the project to truly understand the impact of the project on tenants, its success in achieving its aims and how it might be improved for next time. The methodology should provide a before and after picture, and include temperature and humidity assessments, energy consumption data and EPC data.

- Multiple buildings: In projects involving large or multiple buildings, delivering at least one building as a pilot helps identify and address any challenges. Rolling the installations out in one building helps to reduce disruption and focus tenant support.

- Project management and costs: If you plan to procure a project manager, involving them from the outset means that they can support with application writing. It should be noted that there may be a cost to this, which should be taken into account. Consider aspects such as planning permission requirements, meter changes and electricity grid upgrades at an early stage to avoid unexpected costs.

Appendix / Appendices

Methodology

Case study selection criteria

The following lays out the criteria by which the case study selection was made.

|

Priority |

Criteria |

Reasoning |

|

1 |

Evaluation Reports |

Aimed to select case studies that had data available to provide information about the impact of the project. |

|

2 |

ZDEH Solution |

Providing case studies with a mix of ZDEH solutions will be useful for a wide range of social landlords. |

|

3 |

Funding sources |

We want to highlight that a range of funding sources are available but are aware that these can change, so focused on examples most relevant to social landlords. |

|

4 |

Archetypes |

It is key to have a range of housing types represented so that the case studies are relevant for social landlords with diverse properties. |

|

5 |

Landlord type |

A range of social landlords will help engage varied groups and increase the relatability and therefore impact of the case studies. |

|

6 |

Other measures |

Providing insights into other measures will help landlords to consider the energy efficiency of the whole property. |

|

7 |

Delivery agents and installers |

To ensure a non-biased view of delivery and the challenges associated. |

|

8 |

Project costs |

By prioritising criteria such as a range of housing type and solutions used, we will collate data on varied project costs. |

|

9 |

Location |

Aimed to include a diverse range of locations to represent the diverse urban and rural install experience, as this can impact the associated challenges. However, other aspects such as housing type will be prioritised, as we expect the range of case studies to be applicable to different locations in Scotland overall. |

Overview case study selection process and limitations

A list of potential case studies was compiled based on an online search, which included publicly available funding reports. A call for case studies was shared by the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations on their social media and via their newsletter and an email to their decarbonisation group. Scottish Government also sent out emails to their distribution lists. This resulted in a list of 23 projects which met the research requirements. Eight projects were finally selected based on the selection criteria.

Finding projects with robust evaluation data was a high priority, and it proved to be a significant challenge. Detailed information about the projects’ approach to impact evaluation was not available before the interviews, and each interviewee had a different perspective on what robust evaluation data includes. Additionally, many of the projects have only recently been completed, and data collection is still ongoing in the projects with the most comprehensive evaluation approach.

The case studies cover a limited range of heating systems with an overweight of air source heat pumps. Many examples of other heating systems, such as district heating and ground source heat pumps, were primarily found in new build housing which was out of scope of the research.

Finding examples of projects that include mixed tenures was also challenging as there were few examples that met the research criteria. As a result, the conclusions drawn in this area are limited.

Several of the social landlords had changes to their staff since the project was completed. In some cases, this meant that interviewees were unfamiliar with certain aspects or stages of the project, limiting what information they could pass on.

Interview topic guide

Section 1: Background of the project

1. Can you start by giving me an overview of the project?

Prompts:

- What measures were installed?

- How many properties had measures installed?

- What property archetypes were included? (detached, four-in-a-block, high rise)

- Were all households tenants of the housing association, or were other tenure types included?

2. What motivated your organisation to develop the project?

- Did you complete any (other) energy efficiency upgrades around the same time as this project?

3. How did you determine what measures you wanted to install?

- In particular, why this ZDEH technology?

- Did the archetype of the properties factor into the decision?

- What heating type was in place before?

- Had the properties had any other recent energy efficiency retrofit work done?

4. Can you give a rough timeline of the project?

- I.e. start date, finish date, when did tenant engagement start, when were installs completed

5. What is the current status of the project?

Section 2: Project delivery and practicalities

6. Did you have any challenges associated with delivering the proposed number of installs?

- Did you take any steps to mitigate these issues? If yes:

- What did you do?

- How effective was this?

7. How did you decide on an appropriate contractor for installing the measures?

- Did you have contractors involved in other parts of the project, such as impact evaluation?

8. What approach did you take to engaging with the tenants?

- Would you say it was successful?

- What was the tenants experience of the project overall?

- Can you give an approximate cost of these engagement activities?

Section 3: Financial considerations

9. Did you receive any funding to deliver the project?

- How was the process to access that funding?

- Do you have recommendations for other social landlords regarding funding and the application process?

10. What was the overall cost of the project?

Did you have other funding sources, or was the rest covered entirely by your organisation?

11. Do you know how much of that was associated with the cost of purchasing the equipment, and of installing the measures?

- Did the equipment and installation costs vary based on property size or building archetype? If so, how?

- If mixed-tenure present: Were there any cost variations as a result of the mixed-tenure nature of the scheme?

12. What other costs were there?

- Was there a budget for:

- Tenant engagement activities?

- Monitoring and evaluation?

Section 4: Project impacts

13. Who carried out the evaluation work?

- What was the cost of evaluation?

- Was the cost of evaluation considered when deciding whether to evaluate the project or not?

14. What kind of impact evaluation data was collected as part of the project?

- What was the sample size for each of these methods?

- Was this collected both before and after?

- Did the before and after periods include heating seasons?

15. How did the energy efficiency of the properties change as a result of the decarbonisation project?

- What evidence do you have to support this?

- What was the impact of the measures on the SAP score?

16. Do you know what the impact of the project has been on energy use?

- Were you able to calculate an average change in kWh per property?

- What was the impact of this on tenant fuel bills?

17. Do you have any figures on the carbon savings that resulted from the project?

- If yes, how was this calculated?

18. Do you know what the impact of the measures were on temperature and humidity of the properties?

- Were there any trends seen across the properties?

- Did you calculate average temp and humidity changes that we report in the case study?

19. What was the householders’ experience pre and post installation?

Section 5: Recommendations for future projects and other social landlords

20. What challenges did you experience during the project?

- Were these centered around any particular project stages?

- Were there specific challenges associated with the archetype, tenure, or location of the buildings?

- How did you overcome these challenges?

21. What were the most successful aspects of the project?

- What factors were behind these successes?

22. Do you feel that the project has met its aims? Why/why not?

23. If you were to carry out a similar project in the future, is there anything you would do differently?

Historic funding schemes

UK Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund Demonstrator

Three Scottish projects included. The current fund is England-only.

Non-domestic Renewable Heat Incentive

Now closed. One project applied but did not get it due to mistake on application.

© Published by Changeworks, 2024 on behalf of ClimateXChange. All rights reserved.

While every effort is made to ensure the information in this report is accurate, no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors, omissions or misleading statements. The views expressed represent those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of the host institutions or funders.

NB. As set out in the Heat in Buildings Strategy, the Scottish Government is progressing work on the reform of EPCs. A consultation on this topic closed in October 2023. The reform proposes to introduce new metrics that, among other things, separate out fabric efficiency and cost, and carbon emissions. ↑

Scottish Government (2023) Social housing net zero standard: consultation ↑

Climate Change Committee (2023) Letter: Reform of domestic EPC rating metrics to Patrick Harvie MSP ↑

Scottish Government (2023) Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) reform: consultation ↑

This research focuses on specific criteria therefore this case sample is not representative of the success and outcomes of the SHNZHF overall. The SHNZHF was originally part of the LCITP. The SHNZHF is an ongoing programme whereas the LCITP has closed. ↑

This research focuses on specific criteria therefore this case sample is not representative of the success and outcomes of the LCITP overall. ↑

Formerly ‘Energy Efficient Scotland: Area Based Schemes’ or EES:ABS ↑

Scottish Government (2023) Area-Based Schemes ↑

Scottish Government (2023) Scotland’s Heat Network Fund: application guidance ↑

European Heat Pump Association (2023) Heat pumps and high rises: Case studies from across Europe ↑

Ofgem (2023) Ofgem review reveals that customer service standards of energy suppliers must improve ↑

Given the standard nature of the flats, only one pre-install EPC was provided by the social landlord for analysis. ↑