Enabling collaborative landscape management in Scotland – the stakeholder view

Completed in September 2024

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/5006

Executive summary

Purpose

Collaborative landscape management is the enhancement of ecosystems via combined efforts of multiple farmers and land managers across a landscape. It has potential to help meet Scottish Government targets associated with addressing biodiversity loss and climate change.

This research, commissioned by Scottish Government, investigated a variety of models and experiences of collaboration to explore how support for collaborative landscape management in Scotland could be provided. This can help inform how such support may be incorporated in the Agricultural Reform Programme and other relevant policy areas.

Key findings

Overall, stakeholders were keen to see that we build on what exists already, rather than reinventing the wheel.

Relevant examples of collaboration in Scotland:

- Facility for Investment Ready Nature in Scotland (FIRNS)

- Deer Management Groups

- Tweed Forum

- Working for Waders (led by the RSPB)

- Findhorn Watershed Initiative

The English farmer cluster model is also considered successful in bringing farmers together and initiating and planning for collaborative activities. This is beginning to be replicated in Scotland, for instance in Strathmore, Moray, Lunan Burn and West Loch Ness, mainly supported by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust.

International examples:

- Landscape Enterprise Networks (efforts are underway to develop LENs in Leven and elsewhere in Scotland).

- The FASB initiative in Brazil

- The Cevennes National Park in France

- The EU Interreg Partridge project

Success factors, required support and opportunities

Informed by the main success factors in these examples, as well as their own knowledge and experience, stakeholders identified the following support needs:

- Facilitation to bring groups together and enable planning, preparation for and implementation of collaborative landscape management approaches. This includes long-term funding and training for facilitators. This could be provided through a mechanism akin to the Countryside Stewardship Facilitation Fund delivered in England by DEFRA, or expanding the Farm Advisory Service.

- Long-term funding dedicated to incentivising and supporting implementation of collaborative activities. This could include investing in existing collaborative structures, such as farmer clusters, Regional Land Use Partnerships, Landscape Enterprise Networks and Deer Management Groups. Greater accessibility and flexibility of funding are needed to encourage engagement in collaborative landscape management.

- Encouraging private sector investment to incentivise engagement in collaborative landscape management and enable greater flexibility for context-specific, bespoke projects. This could be encouraged by increasing the scale of FIRNS and completing development of NatureScot’s Landscape Scale Natural Capital Tool. The Scottish Government could also actively broker direct connections between farmers and private-sector organisations.

- Training, conferences and knowledge sharing to foster a culture of collaboration.

- Monitoring, evaluation and communication about the benefits of collaborative landscape management approaches. For example, through building on data such as NatureScot’s Ecological Surveys and Natural Capital Tool, as well as community science approaches.

- Coordinated support for collaboration, both across government policies and between government and other stakeholders. Collaboration may be incentivised by increasing support points in the Agri-Environment Climate Scheme and Nature Restoration Fund.

Gaps and opportunities for future research and innovation

We have found tensions between stakeholders’ preferences for greater incentives and the importance of regulation, as well as between simplicity and flexibility of support mechanisms. Private sector involvement may incentivise flexible collaboration. However, approaches that ensure private-sector-led nature restoration initiatives remain responsible and accountable, whilst making favourable returns on investment, need to be explored.

Glossary / Abbreviations table

|

Collaborative landscape management |

Enhancement of ecosystems via the combined efforts of multiple farmers and land managers across a landscape (Westerink et al., 2017). |

|

AECS |

Agri-environment climate scheme |

|

Biodiversity |

The variability among living organisms from all sources including terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services). |

|

CSFF |

Countryside Stewardship Facilitation Fund |

|

DMGs |

Deer Management Groups |

|

ECAF |

Environmental Cooperation Action Fund |

|

Facilitation |

Activities provided by an individual or organisation to run meetings, foster relationships, discussions, planning and learning. May also include coordination of administrative tasks for groups of collaborators (Leach and Sabatier, 2003). |

|

FAS |

Farm Advisory Service |

|

FIRNS |

Facility for Investment Ready Nature in Scotland |

|

GWCT |

Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust |

|

LENS |

Landscape Enterprise Networks |

|

LEAF |

Linking Environment and Farming |

|

Natural capital |

Defined by NatureScot as: A term for the habitats and ecosystems that provide social, environmental and economic benefits to humans. |

|

NGOs |

Non-governmental organisations |

|

NRF |

Nature Restoration Fund |

|

RLUPs |

Regional Land Use Partnerships |

|

RSPB |

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds |

|

SAOS |

Scottish Agricultural Organisation Society |

|

SAC |

The Scottish Agriculture Consultants |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the stakeholders who participated in this study, Antonia Boyce for review and project management support, and Alhassan Ibrahim for review.

Introduction

Context

It is widely acknowledged that transformative change is needed to address biodiversity loss and climate change at pace and at scale. The Scottish Government has therefore set ambitious targets to meet ‘Net Zero’ by 2045 and proposed nature restoration targets for the same period, for inclusion in a Natural Environment Bill. Meeting these targets will require collaboration across the boundaries of individual farms and land holdings, to match land management to the scale of habitats, catchments, and landscapes.

Defining collaborative landscape management

Various definitions of collaborative landscape management exist. For the purpose of this report, we use the definition: enhancement of ecosystems via the combined efforts of multiple farmers and land managers across a landscape (Westerink et al., 2017). Academic literature indicates such approaches can enable positive outcomes for nature and climate change (Kuhfuss et al., 2019), increasing information flows and learning (Prager and Creaney, 2017), as well as reducing the likelihood of conflicting or duplicate efforts by neighbours (Westerink et al., 2017). In so doing, they may offer better value for public money.

However, it cannot be assumed that farmers and land managers are able and willing to collaborate across a landscape. Collaboration requires time and effort. Support mechanisms such as agri-environment schemes have historically been directed at the level of individual farms, rather than at the landscape scale. Scottish Government are therefore keen to understand more about how to create a supportive policy environment for collaborative land management practices.

Existing research on collaboration between farmers indicates that it often depends on long-term relationships and knowledge-sharing, supported by facilitators (Kuhfuss et al., 2019). Where farmer groups already exist, their facilitators are known to be a key influence on farmers’ learning (Prager and Creaney, 2017). The importance of facilitators is also true for other types of landscape-scale collaborations (Waylen et al., 2023). This is especially relevant as other types of landscape-scale partnerships also exist in Scotland, such as Rural Land Use Partnerships (RLUPs), Deer Management Groups (DMGs), and voluntary catchment management partnerships. Ongoing research on collaborative management interventions (JHI-D4-1[1]), in the Scottish Government’s Strategic Research Programme also emphasises the importance of peer-to-peer learning and building on social capital.

There are therefore a variety of models and experiences of collaboration, from which lessons may be drawn. To enable collaborative landscape management for conservation and climate change outcomes, it is therefore important to identify what existing networks and institutions can be built on and how. This will help to establish what approach(es) for supporting collaborative landscape management will be most worthwhile, and feasible, to include in the future agricultural support framework and other policy developments. To assist in understanding how collaborative landscape management can best be supported, the Scottish Government commissioned this CXC study, in which we built on key concepts and insights from the academic literature and explored this issue with key expert stakeholders in Scotland.

Aim

This study engaged with agricultural and conservation stakeholders (including farmers, land managers, conservationists, and academic experts), in Scotland. We explored their expert opinions regarding how collaborative landscape management can be supported to deliver positive outcomes for climate and nature in Scotland. Specifically, we addressed the following research questions:

- What examples of effective support for collaborative landscape scale activities may be identified and what lessons may be learned from them?

- What should support measures look like, to enable farmers and land-managers to engage in collaborative landscape management? What are their relative advantages and disadvantages? How might they enrich and elaborate on existing approaches?

- What are the barriers and opportunities for uptake of collaborative landscape management?

- What benefits can collaborative approaches achieve, and how may they be monitored and evaluated?

The research involved stakeholder engagement through an online survey and in-person workshop, both conducted in June 2024. The methodology is explained in Appendix A.

Stakeholders’ experiences of collaborative landscape management

Stakeholders were keen to emphasise the importance of building on what exists already, rather than ‘reinventing the wheel’. This section therefore identifies existing examples of collaborative landscape management and draws lessons from them in terms of what is working well and what is challenging.

Examples of success

Stakeholders identified a range of examples of collaborative landscape approaches that they perceived as successful, within Scotland, across the UK, and internationally. Existing examples in Scotland included the following:

- The Facility for Investment Ready Nature in Scotland (FIRNS), delivered by NatureScot in collaboration with the Scottish Government. FIRNS is currently supporting 29 projects to improve their readiness to attract private sector investment. FIRNS is also stimulating flows of information and relationship-building via its ‘Community of Practice’ forum.

- The Deer Management Groups are helping to pool information about landscape-scale biodiversity and are encouraging collaboration by bringing people together to work on a common issue (deer management). Groups are entirely different in composition but all work at landscape scale. Initially, this was primarily to manage a single resource (deer), but over the last ten years there has been a shift towards landscape planning in the public interest, including peatland restoration, woodlands and communities. These collaborative mechanisms have been well established but are currently facing a lack of funding for continuation of this work.

- The Tweed Forum are carrying out a great amount of work around river management through building trust among different stakeholders, to engage them in landscape-scale nature restoration. They have successfully improved water quality at the catchment scale, via a collaborative approach.

- The Working for Waders initiative in Strathspey is an example of an environmental NGO funded landscape scale project. It involves a range of different stakeholders, including farmers and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), to protect and restore habitat for waders in Scotland.

- The ‘Findhorn Watershed Initiative’ have achieved success in winning Just Transition funding to support building partnerships among different stakeholders for collaborative landscape management approaches. This funding allows for not just the restoration work but also building social capital and socio-economic aspects.

- The Dee Invasive Non-Native Species Project (DINNs) has a lot of farmers working collaboratively and has good examples of large-scale projects that have achieved funding with relative ease. They were described as ‘doing what they say on the tin’ within their work, one example being bringing people together to collaborate on the removal of Himalayan Balsam (an invasive plant species) in their landscape.

- The Cairngorms Nature Index (CNI), built on an example from The Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), collects data around health of habitats, species and ecosystems and attempts to put it into a standardised format that people can draw on. This has potential to inform clusters in the areas, however this link is not currently there.

The main example from England, which stakeholders spoke highly of, was farmer clusters:

- Farmer clusters are showing success in bringing farmers together and initiating and planning for collaborative activities. This is especially the case where they receive support from the Countryside Stewardship Facilitation Fund (CSFF) delivered by DEFRA. The CSFF supports the time and resources needed for facilitators to arrange meetings, create opportunities for information sharing and conduct administrative tasks. Specific examples that participants mentioned, included the North East Cotswold Farmer Cluster and the Selborne Landscape Partnership.

A wide range of international examples of collaborative landscape management were cited. The full list is included in Appendix B. Some key examples included:

- Landscape Enterprise Networks are helping to build networks of farmers and land managers in multiple countries.

- The FASB initiative in Brazil is supporting local-level nature restoration initiatives by creating collaborative working groups, facilitating peer-to-peer learning, and supporting existing local-level initiatives.

- The Cevennes National Park in France is achieving strong engagement from landowners, by working hand-in-hand with them.

- The EU Interreg Partridge project was considered successful in ensuring consistency for managing species across landscapes.

- The Netherlands is generally considered to have a strong culture of collaboration among farmers. Indeed, collaboration is compulsory for some types of agricultural support.

What is working well?

We draw the following lessons from the above examples of success, regarding what is working well in supporting collaborative landscape management.

Facilitation

The examples of success emphasise the importance of providing a forum for groups of farmers, land managers and other stakeholders to come together in the first place, share ideas, plan and build trusting relationships. One survey respondent emphasised the importance of leadership and building trust: “…a note about how important it is to have trusted people in the area you’re working in, well respected. Leadership and trust is important.” Farmer clusters have been particularly successful in England for encouraging local collaboration between landowners. The perceived success of these English farmer clusters was largely attributed to the fact they can benefit from the CSFF, which supports the time and resources needed for facilitators to arrange meetings, create opportunities for information sharing and conduct administrative tasks. This can help bring farmers and land managers together, in the first place, to agree objectives and plan for long-term and evolving goals/projects to maintain engagement within the group.

Bespoke projects

Bringing groups of farmers and land managers together around a specific, common issue can be particularly effective, as this helps provide a clear reason and motivation for why collaborative landscape management is needed. If different farmers and land managers are able to relate with each other around challenges that they are facing, this can encourage strong relationships between them. The Tweed Forum was raised, by both conservation organisations and farmers, as an example of positive work being carried out around river management. It has focused on bringing local land managers and farmers together to tackle issues such as water quality and run-off. Their approach centres on strong leadership and trust building. Similarly, the Riverwoods project was mentioned as a successful network working towards creation of riverbank woodlands and healthy river systems across Scotland. The Deer Management Groups described themselves as a particular example of a bespoke arrangement, in that they bring people together to work on the specific issue of deer management. “… we represent 50 deer management groups which cover something like 3 million hectares of the uplands, the groups are entirely different in composition but all of them working at landscape scale, initially to manage a resource, which was deer”. Other examples that focused on management of a particular issue included management of beavers, management of habitats for partridge in the EU Interreg project, and removal of Himalayan Balsam in the Dee catchment. A farmer representative used these examples to argue that one-size-fits-all approaches are not always appropriate. He thus emphasised the importance of tailoring collaborative landscape management to specific contexts.

Forums for sharing and learning

Forums for sharing knowledge and experience were considered factors for success in several of the examples above. Such forums can help communicate the benefits of collaborative landscape management, as well as enable learning that could help others to achieve these benefits elsewhere. The FIRNS ‘Community of Practice’ was considered a useful forum by many stakeholders. This focuses on ensuring farmers, land managers and other stakeholders are informed and able to engage in, and see benefits from, environmental markets and private investment in natural capital. For instance, a representative from Bioregioning Tayside suggested that the “community of practice model has been very effective across Scotland and a smaller ‘sister’ fund to FIRNS would be helpful”. A Leven LENS representative stressed that whilst the term ‘communities of practice’ has become a slight buzzword, communities of practice are really important for building channels of communication. Examples of other successful forums included ‘study tours’ (in which farmers visit others in another location to share knowledge and learning), the CSFF conference in England, and the Farm Advisory Service (FAS), which helps farmers to stay informed of new initiatives as they come onstream.

Integrated support

Involving various stakeholder groups in supporting collaborative landscape management was also a factor in the success of the examples above. This includes involving stakeholders beyond just government and the agriculture sector. For instance, LENS are bringing private and public-sector organisations together to broker negotiations, and eventually transactions for organising the buying and selling of nature-based solutions. The Working with Waders project is achieving success in Strathspey, through funding from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and collaboration between NGOs and farmers. Projects like this show that NGOs are willing to collaborate on and fund projects, and that involving a wide range of stakeholders can generally increase capacity for collaborative landscape management in Scotland.

What is challenging?

The catalogue of successful examples of collaborative landscape management signifies that there is a breadth of positive collaboration taking place, which may be learned from and built upon. However, stakeholders also highlighted significant challenges faced for promoting collaborative landscape management approaches, which are explained as follows.

Inadequate facilitation and limited culture of collaboration

Stakeholders perceived poor facilitation and poor communication as preventative to collaboration. For long-term collaboration to work, stakeholders considered the choice of facilitator and engagement methods as key, suggesting consultations cannot be the only engagement method moving forwards. Collaborative projects benefit from a trustworthy, engaging, non-biased and pragmatic facilitator, who regularly stays in touch with participants and is willing to adapt their facilitation method based on the group’s needs. In the workshop, stakeholders perceived that support for facilitation is currently limited, which limits the availability of skilled facilitators to effectively support collaborations.

Stakeholders acknowledged that there is not generally a culture of collaboration between different farmers and land managers, or between the different government and non-governmental sectors involved in supporting collaborative landscape management, due to a historical culture of competition. The current competitive culture results in situations where new approaches, data and technologies are being copyrighted for individual financial gain, rather than shared and used collaboratively with other farmers and landowners for common benefit. Stakeholders in the survey, suggested this can result in hesitancy to engage and trust in new processes, as well as lose out on the benefits of collaboration between different sectors and organisations. For example, the projects listed in Section 5.1 show that NGOs are willing to work with farmers to fund and support collaborative projects. However, they do not currently benefit from agricultural support, which could widen their impact.

Unsuitable funding mechanisms

Our findings revealed a perception, among stakeholders, that current agricultural support is not suitable for supporting collaborative landscape management. Stakeholders consider existing agricultural support, particularly Agri-Environment Climate Scheme (AECS) and Nature Restoration Fund payments, as complicated, restrictive and competitive. This was considered a challenge for engaging in any kind of positive management for biodiversity and the climate, including collaborative approaches. According to stakeholders, the process of acquiring funding has a tendency to be extremely complex and time consuming, with ineffective mechanisms for distributing or releasing funds in a timely manner. Stakeholders also indicated that there is a lack of legal and legislative knowledge amongst farmers and landowners, and this is limiting their ability to apply for funding. Applications for funding, therefore, require a huge amount of effort and monetary investment. Indeed, the costs of initiating collaborations and preparing applications for grants and incentives, were considered significant challenges for engaging in collaborative landscape management. For example, a representative from the Deer Management Groups cited the financial burden of simply preparing an application as a major disincentive for farmers to engage in collaborative landscape management.

Stakeholders considered the competitive nature of funding to exacerbate this, as there are significant costs involved in starting-up and applying for funding, but limited chance of success. Farmer representatives, in particular, agreed that when funding is competitive many farmers simply will not bother applying, as the high cost of applications, combined with the high risk of failure, simply makes it not worthwhile. Multiple stakeholders agreed this structure puts smaller farmers and land managers at a disadvantage and favours large landowners, who have sufficient time and resources for making applications and absorbing fines that could occur through mistakes.

Stakeholders also perceived that, with the exception of getting extra points for collaborative projects in AECS, there is currently a lack of funding designed specifically to support collaboration. Stakeholders expressed concerns that existing grant funding is short term in nature (e.g. for AECS is only a 5-year agreement), which does not lend itself to building collaborations or implementing long term changes at a landscape scale. Additionally, AECS funding is points-based, meaning farmers are in competition with each other to meet the points threshold. This was considered a disincentive to engaging in collaboration.

Existing mechanisms for supporting collaboration were also considered too restrictive, in terms of the types of landscape management options that could be funded. Stakeholders emphasised that a one-size-fits-all approach will never work, and policy support for collaborative landscape management must take this into account. A farmer representative highlighted the geographic differences across landscapes and catchments. He emphasised that even the top of a hill and the bottom of the hill can be very different, and different landowners will have different needs. This is true not just of the physical landscape but also in farming techniques, revenue, or funding streams. As one survey response stated: “Single outcome objectives can limit participation and success”.

Siloed and top-down governance

Stakeholders raised further challenges, related to the approach taken by government, that they thought were hindering support for collaborative landscape management. In the workshop, although farmer representatives stated that the Government has been very imaginative, and that successes should not be forgotten, they also highlighted shortcomings in the Government’s approach. Stakeholders expressed a sentiment that the Government have not listened to them enough, despite continually providing feedback. They perceived this top-down approach from government as perpetuating power imbalances that favour some views about land use and management, over others, and do not offer any real help for farmers.

There was also a feeling that current policy exists in a siloed system in which agriculture, forestry and biodiversity policy do not interact. This can result in complexity and contested interests between different siloes and thus reduce political will and ability to act in support of collaborative landscape management. Some stakeholders, such as a representative from Scottish Environment LINK in the workshop, thought that existing initiatives were “very messy at the government level”. He argued that there are too many different targets and proposed initiatives, which, at the level of implementation at the landscape scale: “no one knows how it is supposed to fit together”. Some agricultural stakeholders also suggested that policies such as the Wildlife Bill and the Land Reform Agenda actually discourage collaboration, because they encourage fragmentation of land ownership.

Limited evidence for the benefits of collaborative landscape management

Stakeholders highlighted that there is limited awareness of successful examples of collaborative landscape management projects and their impacts. They considered this a barrier to promoting favourable attitudes and motivations for collaborative landscape management approaches. It is not always possible to imagine something you have never seen, and positive examples are needed for farmers and land managers to understand the potential benefits of collaborative landscape management. For example, a representative from Bioregioning Tayside felt that a lack of awareness around existing solutions has led to a lack of comprehension around how land could be managed to help deal with extreme weather events. Some stakeholders also highlighted successful landscape collaboration projects along the River Spey and the River Dee, but stressed that their impacts are limited by a lack of communication and knowledge-sharing amongst one another.

Stakeholders’ needs and aspirations for collaborative landscape management

Stakeholders were forthcoming in suggesting the types of support that they thought would enable and enhance collaborative landscape management. This section discusses the types of support that were suggested, as well as potential opportunities that could be taken.

What types of support are needed?

Stakeholders suggested a range of support mechanisms that they thought would help to deliver positive outcomes for climate and nature in Scotland

Support for facilitation of collaboration

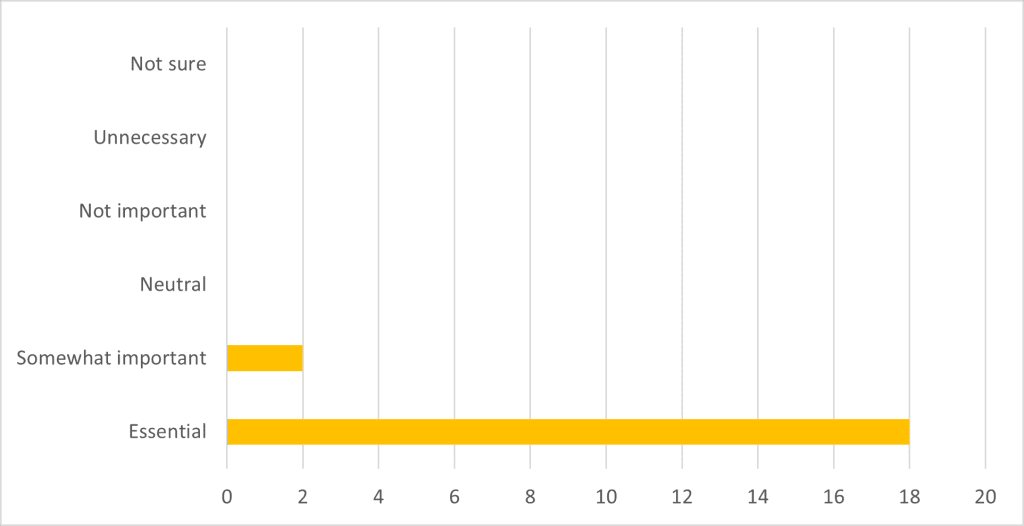

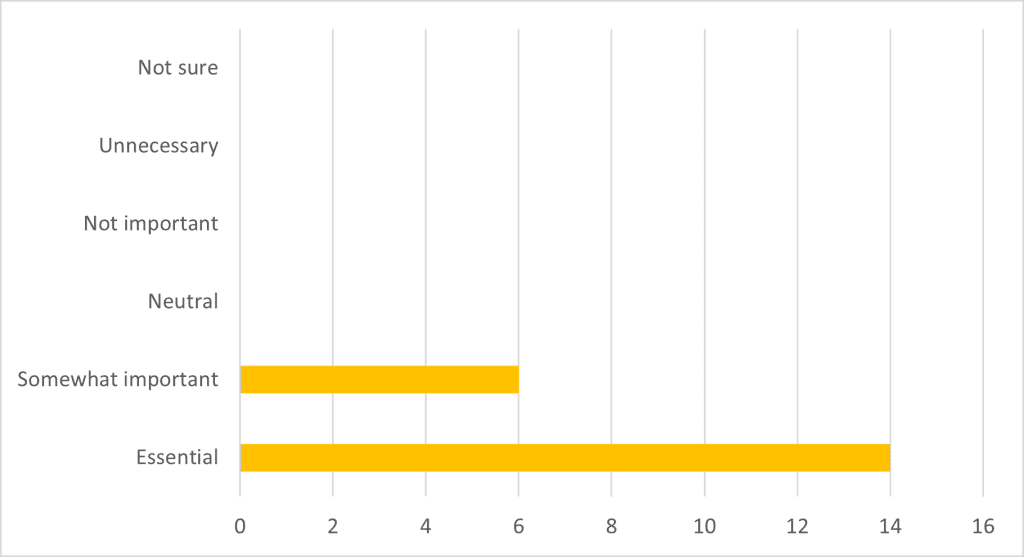

Stakeholders considered facilitation as essential for organising collaborative landscape management approaches. This was considered important by stakeholders from across the range of perspectives represented in both the workshop and the survey. When asked how important facilitation of collaboration was for collaborative landscape management, 17 of 20 survey respondents agreed it was essential, with the remaining 3 suggesting it was somewhat important, as shown in Figure 1.

Facilitators can help, practically, to bring farmers and land managers together, from across a landscape, and help them to form groups that engage in collaborative activities together. In the survey responses, farmers, in particular, emphasised the importance of facilitators engaging with individuals, not just in a group setting, providing opportunities for social interaction, and establishing the conditions under which groups of farmers would be willing to collaborate. Others emphasised the importance of facilitators for building trust and long-term relationships, and who listen to and understand local needs and aspirations. For instance, a representative of a conservation NGO, stated: “To enable the group to come together and get underway, there needs to be a person who is good at bringing the group together and keeping them together.”

Facilitators were considered useful for helping groups of farmers and land managers set clear goals and expectations, incorporating different individual goals and expectations. This was emphasised by another representative of a conservation NGO in the survey: “There needs to be clear objectives and purpose established from the start, so everyone is clear as to why they are collaborating and what outcomes are expected. There should be a clear project plan with clear timelines”. In the workshop, it was suggested that encouraging facilitators to develop formally constituted agreements with groups they work with, can help encourage those groups to take risks associated with collaboration.

Stakeholders also thought that facilitators can help build the capacity of groups to ‘get things done’. This includes helping farmers and land managers to collect data for assessing biodiversity on their land, and then preparing maps and models of collaborative projects and their intended effects. It also includes supporting applications for funding to support collaborative landscape management projects, by conveying information and guidance about funding schemes, and then ensuring applications are prepared correctly, and in a professional format (which one existing farmer cluster facilitator stressed as highly important when groups are first starting up).

Stakeholders recognised that effective facilitation requires skilled individuals and appropriate investment in their training, time and resources. Facilitators need a wide-ranging set of skills, including: project management, mapping, monitoring and evaluation, diplomacy to manage competing interests, awareness of funding schemes, experience of funding applications, a combined understanding of both agricultural economics and biodiversity, and an ability to draw information from across relevant sectors. Stakeholders therefore stressed that facilitators themselves need to be supported, through training, and funding to pay for their time, skills and training.

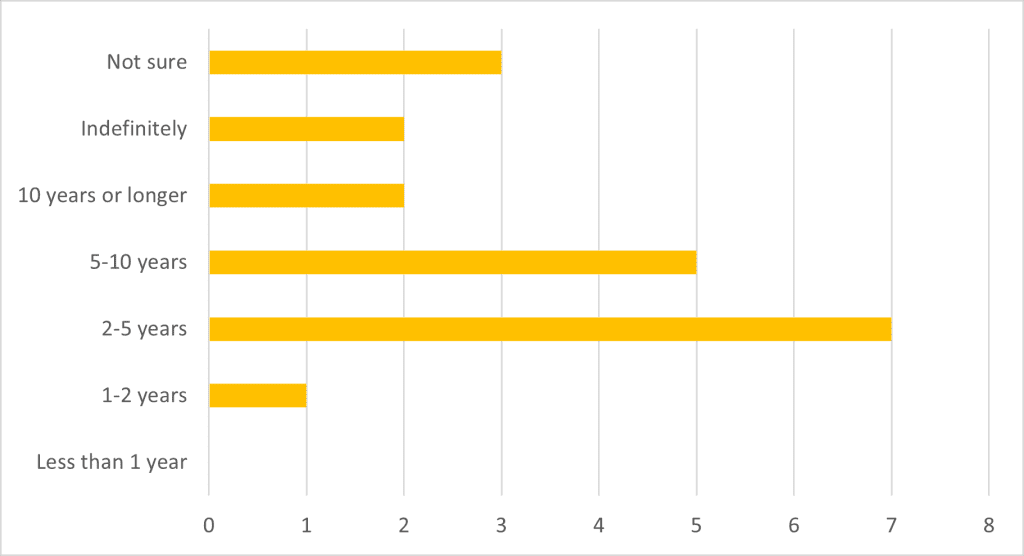

In the survey, we asked stakeholders how long they thought support for facilitation of collaborative landscape management projects should last. As shown in Figure 2, the highest proportion of respondents thought support for facilitation should last 2-5 years (n=7), and the second highest proportion thought support should last 5-10 years (n=5). This emphasises the value of long-term support for facilitation.

Funding to incentivise and implement collaborative activities

Perhaps unsurprisingly stakeholders, across the board, considered financial incentives and funding for implementation as imperative for supporting farmers and land managers to engage in collaborative landscape management activities. As noted in Section 5.3, stakeholders considered existing agricultural support schemes, such as Agri-Environment Climate Schemes (AECS) and Nature Restoration Fund (NRF) as currently unsuited for supporting collaboration. There was therefore a strong push for ‘holistic’ funding for landscape-scale collaboration that would cover support for the full range of different aspects involved in collaborative landscape management. This included:

- Start-up funding to help form groups in the first place.

- Capital funding to help groups acquire resources, such as machinery, and other materials needed to implement a collaborative project.

- Revenue funding for ongoing land management.

- Funding for tasks such as mapping and surveying biodiversity.

- Funding for administrative tasks such as writing and formatting applications.

- Funding for monitoring, evaluation and knowledge sharing.

- Funding for communications and publicity.

Farmers, especially, stressed financial incentives as the single most important support measure for encouraging collaborative landscape management. However, they suggested that it is essential for funding to align with farmers’ interests, rather than simply being lucrative. In the workshop, one cluster farmer stated, strongly: “the motivation to do the best for the environment is there, but the support is not coming. The government need to up their game and provide incentives. Farmers will go along, as long as they are paid, but we need help to do that”.

All stakeholders did recognise, however, that such holistic funding for collaborative landscape management would be expensive, and thus thought it would be challenging for public sector funding alone to provide this. In both the survey and the workshop, stakeholders showed interest in private sector investment as an alternative, or additional, source of funding for supporting collaborative landscape management. One advantage of this, that stakeholders identified, is that many businesses already have environmental targets and are ready and willing to invest in efforts to improve biodiversity and climate change outcomes. This may be for financial benefits (through nature finance), or to improve their reputation. Representatives from the Deer Management Groups and LENS explained that they are already working successfully with investment from private businesses, whilst several stakeholders cited FIRNS as an initiative that could help to build opportunities for private sector investment. One stakeholder, from Bioregioning Tayside, suggested that the government could encourage access to private sector funding by facilitating direct connections between groups of farmers and corporations with an interest in investing in them (such as large supermarkets). Another stakeholder, from a land agency cautioned about over-reliance on the private sector, noting that private sector investment is profit-driven and can make nature a marketable commodity.

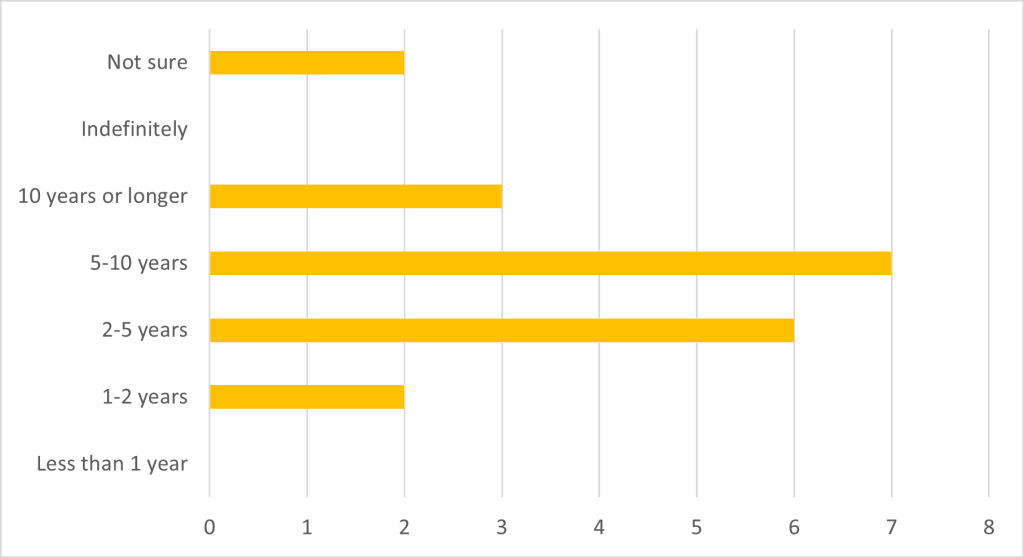

The survey asked respondents to rank the importance of support for implementation of a collaborative landscape management project, shown in Figure 3. The highest proportion thought support should last 5-10 years (n=7) and the second highest proportion thought it should last for 2-5 years (n=6). This indicates the importance of medium-to-long-term support for collaborative landscape management projects to be successful.

Education and advocacy

Whilst there was universal agreement on the importance of financial incentives, in the workshop, several stakeholders noted the importance of creating longer-term changes in attitudes and behaviour. Some stakeholders suggested that farmers, land managers, and others whose businesses depend on land and agriculture, need to understand the potential benefits of collaborative approaches to nature restoration for their business models. For example, crop production benefits from the presence of pollinating insects, so there is an inherent benefit to crop farmers managing land to protect those insects at the landscape scale. One stakeholder even questioned whether farmers and land managers should receive payment in instances where biodiversity is good for their businesses. However, there was some disagreement with this, especially from farmers, who argued that they already have the knowledge and motivation for nature restoration, they just need the funding.

Increasing flows of knowledge, information and learning about the benefits of biodiversity emerged as an important incentive, in addition to funding. This was considered a potential opportunity to encourage longer-term changes in attitudes and motivations that would promote management of land for positive nature restoration and climate change outcomes. Such changes could reduce dependence on financial incentives for collaborative landscape management. This emphasises the importance of increasing the visibility of successful collaborative projects, including through communication between projects and increasing opportunities for advocacy and information sharing.

Collaborative culture

In the workshop, several stakeholders suggested ways in which a collaborative culture may be encouraged in Scotland. A farmer representative pointed to the French agricultural support system as a positive example of a collaboration being encouraged. There was also some discussion around the idea that collaboration could be made compulsory to ensure it happens. A farmer representative asserted that this could be necessary, because in cases where voluntary schemes for collaboration have ended, collaborative action has stopped, or even been reversed. Such a compulsory approach is taken in the Netherlands, where there is a long history of group/cluster development, apparently with some success. However, for a compulsory approach to be successful in Scotland, stakeholders thought there would be a need for major group development across farmers and land managers. The idea of a compulsory approach was also criticised by a land agent, who thought it would be politically undesirable to implement and enforce. A representative from Scottish Land and Estates suggested a culture of collaboration could be created through a compromise of points-based awards for collaboration within Tier 2 agricultural support payments and then making collaboration compulsory in Tier 3 support. This was contested by a conservation NGO, as points for collaboration already exist in AECS and the NRF. Nonetheless, these points systems could be increased in scale, to incentivise collaborative activities.

Simplicity and flexibility.

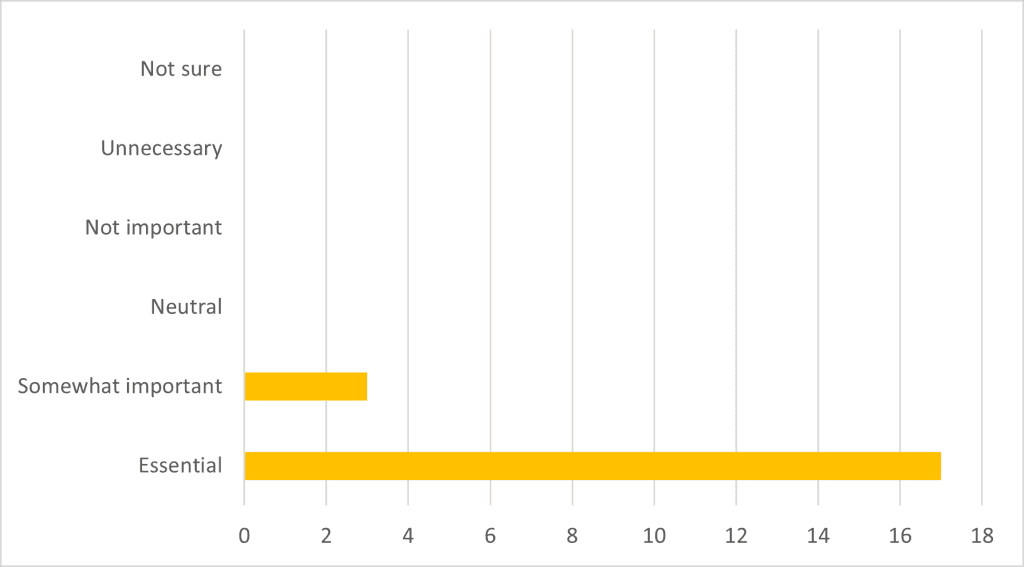

As explained in Section 5.3, there was a strong sentiment, across all of the participating stakeholders, that current support measures, such as AECS, are too complicated to effectively support collaborative landscape management. There is therefore huge demand for simplified application processes. As shown in Figure 4, 17 survey respondents considered the accessibility of application processes to be essential, whilst the remaining 3 considered it somewhat important.

Stakeholders also wanted to see greater flexibility, in terms of the types of landscape management options for biodiversity restoration that farmers can access support for. Stakeholders highlighted a need for different types of collaboration in different landscapes for different purposes, and a need for bespoke funding, information and facilitation to be tailored to different contexts. For example, one representative from Bioregioning Tayside called for measures that “allow for agency and different interpretations, depending on context.” Similarly, one member of a farmer cluster suggested a need for different measures, and different governance structures, for collaboration in different regions, citing an example from France, in which different regions are supported in different ways. Another cluster farmer contended that flexibility is needed within specific landscapes, not just across different regions, and suggested that support measures could be tailored to specific habitats. Specific options that stakeholders wanted to see funding for included: planting trees, using grasslands to sequester carbon, mixed livestock and forest farming, reducing fertiliser use, and adoption of hydrogen as a fuel.

There were also calls for flexibility in terms of allowing for the fact that mistakes might be made during the implementation of collaborative landscape management approaches. Farmers were keen not to be punished too harshly for this and thought greater lenience would help reduce the risk of them engaging in collaborative landscape management. This was considered especially important for encouraging smaller farmers and land managers to engage in nature restoration. Stakeholders from Scottish Agricultural Organisation Society (SAOS) and Bioregioning Tayside thought the government needed to ‘let go’ of its risk aversion and accept that not all projects will work.

These calls for simplicity and flexibility must, obviously, be measured against a need for regulation and accountability, to ensure that collaborative landscape management is done effectively and makes best use of public funds. This was acknowledged by stakeholders, to some extent, though there was a strong push to favour flexibility and incentives over regulation. There is also a potential tension between demands for flexibility and demands for simplicity. The greater the variety of options that are offered, the greater the complexity of support required.

Integrated approach

Stakeholders indicated a need for clear and joined-up support and advice from Scottish Government. In the survey, 16 out of 20 survey respondents felt that navigating complex and contested interests and priorities was essential, the remaining 4 felt it was somewhat important, as shown in Figure 5, below.

Taking an integrated approach to designing and implementing support, as well as governance of collaborative landscape management was considered a solution that could help navigate this complexity and contestation, as well as balance flexibility with accountability and simplicity. Stakeholders strongly suggested that for policies to successfully support collaborative landscape management, they must be joined-up and ensure they complement each other. To aid this, stakeholders wanted to see greater integration of different sectors, policies and government departments, as well as regular and meaningful engagement with stakeholders, to listen to their needs. For example, non-governmental organisations, such as the RPSB, LENs, Bioregioning Tayside and the Deer Management Groups, who are already doing collaborative work with farmers and land managers at a landscape scale, stated they would benefit from increased collaboration with the government and agricultural sector. Such a collaborative approach was perceived, by stakeholders, as advantageous, because working across sectors could help to improve simplicity and efficiency of support for collaborative land management, as well as build on existing efforts to increase the scale of collaborative landscape management. However, there could be a danger that involvement of other sectors could diminish support for agriculture. Some stakeholders were therefore careful to ensure that agricultural funding stays ringfenced.

Monitoring, evaluation and knowledge-sharing

Stakeholders also emphasised the importance of support for monitoring and evaluation of collaborative landscape management approaches. In particular, they thought this should involve support for understanding and mapping the biodiversity that exists in a landscape, and then assessing the impacts of collaborative projects on this biodiversity, over time. Stakeholders suggested a range of approaches for understanding the success or efficacy of collaborative landscape management projects. This included more informal opportunities for learning and sharing knowledge, as well as more structured approaches to formal monitoring and evaluation. In terms of learning and sharing knowledge, ‘study tours’ (where groups of farmers visit farmers in another location to learn from each other), and forums such as conferences and the FIRNS ‘community of practice’, were considered important for encouraging reflection and learning about collaborative landscape management. Stakeholders suggested several potential benefits of such opportunities for learning and sharing knowledge. In the workshop, one land agent thought they could help farmers and land managers understand what work is needed to manage landscapes for nature restoration in their local areas, and understanding how collaborations may be set up. A cluster farmer thought they could be used for sharing how business and funding decisions and agreements are made.

In terms of more formal, or structured, monitoring and evaluation, the importance of setting ‘baselines’ and maps of the biodiversity that exists in a landscape, at the start of a project, were considered essential by a range of stakeholders in both the survey and the workshop. For instance, a survey respondent from a conservation NGO stated that monitoring and evaluation should be conducted: “on a project scale by establishing the baseline and then how the project has moved beyond this”. In other words, farmers and land managers should establish what biodiversity exists in a landscape at the outset of a project, and then assess the success of the project according to whether and by how much biodiversity improves during the implementation of the project. This was reflected by similar suggestions across the survey and the workshop, with stakeholders indicating a need for farmers to be assisted in producing such baselines and associated maps. However, a GWCT representative in the workshop contended that such baselines of biodiversity need to be conducted at the level of individual farms, before they can be done at the landscape scale.

As is often the case when discussing approaches for monitoring and evaluation, there was tension between assessing standardised indicators of biodiversity and exploring more contextual, qualitative experiences. In the survey, several respondents, across different perspectives, called for monitoring and evaluation in relation to general standards of biodiversity, such as standardised ‘measurement, recording and verification’ frameworks. In contrast, other survey respondents emphasised the importance of context-specific monitoring and evaluation that takes specific, landscape-scale objectives into account and includes qualitative data regarding people’s relationships with the landscape and the biodiversity within it. One farmer specifically objected to ‘simplified biodiversity metrics.’ A respondent from a conservation NGO suggested that monitoring and evaluation should include recreational and cultural elements, as well as those related to biodiversity and climate outcomes. This was reflected by the strong sentiment in the workshop around the importance of flexibility and context-specific approaches. Striking a balance between standardised and context-specific approaches to monitoring and evaluation therefore remains a challenge.

Opportunities for supporting collaboration

Further to the needs for support, outlined above, stakeholders suggested several opportunities for improving support for collaborative landscape management. Again, stakeholders were keen to emphasise the importance of building on existing efforts, rather than ‘reinventing the wheel’.

Existing structures for enabling collaboration

Stakeholders suggested several existing initiatives that could be invested in to help consolidate and encourage uptake of collaborative landscape management approaches. Farmer clusters, which were considered a successful example of collaborative landscape management approaches, are beginning to be developed in Scotland. Thus far, these have largely been supported by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, and exist in Strathmore, Moray, Lunan Burn, and West Loch Ness. Efforts are also underway to develop LENs in Leven and elsewhere. Stakeholders also suggested that the Regional Land Use Partnerships and Deer Management Groups already have structures in place for encouraging collaboration, and these could be built upon. Several stakeholders suggested that investment in these existing structures for networking and collaboration should be increased, particularly the Regional Land Use Partnerships (RLUPs) and FIRNS Community of Practice. Funds such as the Just Transition Fund may also be used to support building partnerships, as in the given example of the Findhorn Watershed Initiative.

Funding and training for facilitators

For supporting facilitation, specifically, stakeholders advocated for the English Countryside Stewardship Facilitation Fund’ (CSFF) to be adopted in Scotland. Some also highlighted that some support for facilitation was included in the Environmental Cooperation Action Fund (ECAF), although this closed in 2017, without having issued any funding. Some stakeholders suggested something similar could be incorporated into Scottish Government’s Tier 1 and Tier 2 agricultural support mechanisms. In terms of providing training to create a cadre of skilled facilitators, the Farm Advisory Service (FAS) were considered well-placed to contribute to this. Their services already include communicating and explaining new support schemes as they come online. It was suggested this could be expanded to provide opportunities for learning and training for facilitators, as well as delivering proactive facilitation of collaborative projects.

Incentives and funding for implementation

Stakeholders were keen for funding and financial incentives to support collaborative landscape management approaches. In terms of financial incentives for farmers to engage in collaborative activities, stakeholders considered the current incorporation of points for collaborative projects within Agri-environment Climate Scheme (AECS) payments as a positive, and suggested that the availability of points for collaboration should be expanded. Similarly, several stakeholders suggested including a collaborative element in the Nature Restoration Fund. Incentivising collaborative landscape management within the Basic Payment Scheme was also considered an opportunity.

Private sector investment

Many stakeholders, particularly those representing agri-environment NGOs, acknowledged that providing holistic financial support for collaborative landscape management would be expensive. It may not be possible for such support to be entirely provided by the public sector. Stakeholders were therefore keen to see greater private sector investment to support incentivisation and implementation of collaborative landscape management activities. Conservation NGOs highlighted that current ‘rewilding’ initiatives are already funded mostly through private business, including foreign investors. Exploring similar opportunities to support collaborative landscape management could therefore offer a solution to increasing financial incentives for this.

Various stakeholders highlighted opportunities to incentivise private companies to support collaborative landscape management. Some thought food companies could partner with or invest in collaborative groups of farmers, particularly local businesses operating within the same landscape. This was also thought to result in shorter supply chains, which could further complement biodiversity and climate goals. Others thought larger businesses (such as large supermarkets or chain restaurants) could be encouraged to build reputational capital in Scotland at a large scale, by investing in biodiversity and climate outcomes. Stakeholders highlighted that most businesses now have environmental targets and have an interest in contributing to positive outcomes for nature and climate. However, they still need a push from Government to take the initiative. Some stakeholders thought the role of Scottish Government could be to facilitate direct connections between farmer groups and private sector funders, whilst others suggested mandating companies to conduct ‘nature impact disclosures’ could push them to invest in nature restoration.

Existing initiatives that encourage private sector investment in natural capital were also considered useful for stimulating private sector investment. In particular, stakeholders spoke positively about the Facility for Investment Ready Nature in Scotland (FIRNS), and saw increasing the investment and scale of this as an opportunity for supporting collaborative landscape management. A ‘Landscape Scale Natural Capital Tool’, is also being developed by NatureScot, to assess and value natural capital assets across a landscape. There was a strong appetite, particularly among those representing farmer clusters, for further development of this, in partnership with private companies who have nature restoration goals. Some agricultural stakeholders also highlighted the opportunity for new forms of land tenancy, in which natural capital gets integrated into the value of a farm. They thought this could incentivise groups of farmers to collaborate, to increase the value of natural capital across a landscape.

Advocacy and education

Increasing advocacy, education and information flows was considered a useful approach for highlighting the benefits of collaborative landscape management for nature and climate, as well as businesses that depend on the land for productivity. Several stakeholders suggested that building on the existing approach taken by the FAS could be an opportunity to promote this. The FAS already help to communicate and explain information about new initiatives, as they come onstream. Stakeholders therefore considered them well-placed to facilitate communication and sharing of information about successful examples of collaborative landscape management projects, as well as improving understanding of the benefits of managing landscapes for positive nature and climate outcomes. Other suggested opportunities to increase knowledge and information flows about collaborative landscape management included: advocacy campaigns and training, conferences, ‘study tours’, and ‘place-based apprenticeships’ to increase awareness of environmental challenges for young farmers.

Some agricultural representatives also proposed that the farming media, and events, such as the Royal Highland Show, could do more to communicate the benefits of collaborative landscape management and provide recognition of successful collaborations. Printed, online or, podcast media, particularly those that farmers are actively listening to, represent an opportunity to highlight the need for collaborative landscape management. The wider group was in agreement and a representative from Scottish Land and Estates suggested their ‘Helping it Happen’ awards could incorporate a collaboration category to reward and promote collaborative approaches.

Creating a culture of collaboration

The opportunities presented above emphasise the importance and potential benefits of building on existing initiatives. Stakeholders were keen for a culture of collaboration to be created, in which all stakeholders are involved. Several stakeholders commended this engagement, as a useful step in taking stock of existing collaborations and involving stakeholders in planning support for collaborative landscape management. They were therefore keen for further such engagements. Some stakeholders, such as LENs and the Strathmore Farmer Cluster thought that accreditation of collaborative groups as ‘trusted operators’ would help consolidate their positions and encourage further collaboration. Stakeholders thought that greater integration across policies, as well as across sectors would help encourage collaboration. However, stakeholders acknowledged this is complex and agreed that agricultural support must remain ringfenced.

Monitoring and evaluation

Stakeholders also suggested several existing initiatives that could be built on to assist monitoring and evaluation of collaborative landscape management approaches. Farmer cluster groups were again highlighted as examples of best practice, in this case for developing standards and creating opportunities for data collection. For example, the Strathmore Cluster are currently using hand-held mapping systems for mapping key species. Deer Management Groups were also raised as an existing structure that could help to lead, pool and disseminate data. Similarly, Bioregioning Tayside are using ‘community science’, to involve local communities in monitoring biodiversity in their local area. Stakeholders thought such approaches could be useful for monitoring the effects of collaborative landscape management on biodiversity.

Increasing ‘open access’ to data, mapping and modelling also has the potential to help land managers and communities understand why change is needed. The Landscape Scale Natural Capital Tool, being developed by NatureScot was considered a useful initiative to support access to data. This is taking a holistic approach to recording different elements of a landscape, and their condition, such as soil types, or water quality. This tool could prove useful for understanding and mapping what is needed for positive outcomes for nature and climate, and could be used by collaborative groups to plan and set goals. Open access to such data could also allow groups to feel some ownership over it. However, stakeholders did raise the question of how and by whom data collection and mapping should be paid for. Some emphasised the fact that this too needs to be funded and facilitated.

Other useful data sources that stakeholders suggested, included ecological surveys and apps being rolled out by NatureScot, as part of the Agricultural Reform Programme, and the Linking Environment And Farming (LEAF) Sustainable Farming Review or data platforms like Omnia (a digital information tool for supporting farm management). One participant indicated that mobile apps for recording biodiversity, are being developed for biodiversity credit schemes. Several stakeholders also indicated that bringing in independent reviewers, such as universities and expert ecologists, could help to support monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusions

In this section, we draw conclusions in relation to what is currently working well, what is needed and what opportunities may be built upon for supporting collaborative landscape management. We also highlight some gaps and opportunities for further research and innovation. The conclusions are based on the input from stakeholders in this study. They are particularly relevant to the Scottish Government’s Agricultural Reform Programme but may also be relevant to other groups with resources and capacity to support collaborative landscape management.

What is working well?

It is important to build on existing initiatives and avoid reinventing the wheel. Successful collaborations in Scotland provide examples for how to bring people together and build relationships across landscapes and could thus be supported to build on their existing work. Stakeholders also consider that the English farmer cluster model works well. This is beginning to be replicated in Scotland. The main factors supporting these examples’ success were support for facilitation, bespoke projects that bring people together to work on an issue of common interest, forums for sharing knowledge and experience, and an integrated approach to supporting collaboration.

What support is needed?

Although the examples of success are encouraging, stakeholders thought that collaborative landscape management is currently hindered by limited support for facilitation, scarcity of suitable incentives and funding for implementation, poorly integrated approaches to support, and limited evidence of successful collaborations. Overall, Scotland was considered to lack a collaborative culture among farmers and land managers.

Facilitators are required to bring groups together and enable planning, preparing for and implementation of collaborative landscape management approaches. Support for facilitators is therefore required in the form of training, to develop their skillsets, as well as funding to pay for their time and skills.

Stakeholders also require incentives and long-term funding for development and implementation of collaborative landscape management activities. Encouraging private sector investment could act as an incentive, as well as supplementing public sector funding for implementation of collaborative activities. Balancing accessibility and flexibility of funding, with quality control and regulation, is a challenge, but stakeholders strongly thought that greater accessibility and flexibility are needed to encourage engagement in collaborative landscape management. Support for bespoke projects, perhaps utilising private sector funding, or tailored support for different landscapes and regions could help resolve this.

Education and advocacy are considered necessary to change attitudes and highlight the benefits of collaborative landscape management. This would be aided by support for monitoring and evaluation that demonstrates the effects of collaborative approaches. A culture of collaboration may also be fostered through an integrated approach to supporting collaborative landscape management. Stakeholders are keen for integrated policies within government, as well as involvement of actors beyond those directly involved in government and the agriculture sector.

What opportunities exist?

Existing examples of collaborative structures, such as farmer clusters, Regional Land Use Partnerships, Landscape Enterprise Networks and Deer Management Groups may be used as foundations for future collaborative landscape management approaches. Investing in them could thus help to consolidate and enhance uptake of collaborative landscape management approaches.

Funding for facilitation may be supported by adapting the English Countryside Stewardship Facilitation Fund for Scotland. The approach of the Farm Advisory Service could be elaborated to include training a cadre of skilled facilitators for collaboration.

Incentives for collaboration may be built into the Agri-Environment Climate Scheme and the Nature Restoration Fund, through increasing the points available for collaborative approaches in these schemes. Opportunities exist to increase private sector investment in collaborative landscape management, including increasing the scale of the Facility for Investment Ready Natural Capital in Scotland (FIRNS), and completing development of NatureScot’s Landscape Scale Natural Capital Tool. The Scottish Government could also play a useful role by actively facilitating connections between farmers and private-sector organisations, such as local businesses and larger scale supermarkets and chain restaurants.

Building on existing initiatives and networks could also help foster a culture of collaboration. This could include increasing opportunities for training, conferences and knowledge sharing, as well as communicating the benefits of collaborative landscape management approaches. There is growing access to data, including NatureScot’s Ecological Surveys and their developing Landscape Scale Natural Capital Tool, as well as other sources and types of knowledge, including participatory approaches like Bioregioning Tayside’s community science. These could help improve understanding of the effects of collaborative approaches, whilst promotion of collaborative landscape management approaches via the Farm Advisory Service, farming media and agricultural events could help raise awareness.

Gaps and opportunities for future research and innovation

The results of this project identified several tensions. Stakeholders appeared to prefer encouragement for collaboration via increasing incentives, but there was acknowledgement of the importance of regulation. They also requested both simplicity and flexibility to support context-specific, bespoke projects, but simplicity and flexibility are not always easily enabled together.

Private sector investment may help to increase incentives and provide some of this flexibility, but it will require caution to ensure standards continue to be met. Exploring and testing mechanisms for involving the private sector in a way that ensures responsible and accountable nature restoration, whilst making favourable returns on investment is an important opportunity for research and innovation.

Stakeholders also highlighted the importance of integration across government policies and between government and other stakeholders. However, questions about how such forms of integration may be achieved and who should be responsible for coordinating them, remain unresolved. Further research and innovation on the topic of integration is therefore important.

Although this study identified and engaged with a range of stakeholders and initiatives, the timescale for this project required tight targeting. Further engagement and a more in-depth appraisal would be beneficial. In particular, the 2024 UK General Election hindered engagement with UK Government stakeholders involved in collaborative landscape management approaches. Further engagement with the Farm Advisory Service could also be useful. It may also be enlightening to conduct a more in-depth appraisal of international examples of support for collaborative landscape management.

References

HODGE, I. 2024. The potential for local environmental governance: A case study of Natural Cambridgeshire. Journal for Nature Conservation, 79, 126631.

KUHFUSS, L., BEGG, G., FLANIGAN, S., HAWES, C. & PIRAS, S. 2019. Should agri-environmental schemes aim at coordinat-ing farmers’ pro-environmental practices? A review of the literature.

LEACH, W. & SABATIER, P. 2003. Facilitators, coordinators, and outcomes. Promise and Performance Of Environmental Conflict Resolution. RFF Press.

PRAGER, K. 2015. Agri-environmental collaboratives as bridging organisations in landscape management. Journal of Environmental Management, 161, 375-384.

PRAGER, K. 2022. Implementing policy interventions to support farmer cooperation for environmental benefits. Land Use Policy, 119, 106182.

PRAGER, K. & CREANEY, R. 2017. Achieving on-farm practice change through facilitated group learning: Evaluating the effectiveness of monitor farms and discussion groups. Journal of Rural Studies, 56, 1-11.

RILEY, M., SANGSTER, H., SMITH, H., CHIVERRELL, R. & BOYLE, J. 2018. Will farmers work together for conservation? The potential limits of farmers’ cooperation in agri-environment measures. Land Use Policy, 70, 635-646.

RUNHAAR, H. & POLMAN, N. 2018. Partnering for nature conservation: NGO-farmer collaboration for meadow bird protection in the Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 73, 11-19.

WAYLEN, K. A., BLACKSTOCK, K. L., MARSHALL, K. & JUAREZ-BOURKE, A. 2023. Navigating or adding to complexity? Exploring the role of catchment partnerships in collaborative governance. Sustainability Science, 18, 2533-2548.

WESTERINK, J., JONGENEEL, R., POLMAN, N., PRAGER, K., FRANKS, J., DUPRAZ, P. & METTEPENNINGEN, E. 2017. Collaborative governance arrangements to deliver spatially coordinated agri-environmental management. Land Use Policy, 69, 176-192.

Appendices

Appendix A. Methodology

We began by identifying a conceptual framework of factors likely to enable collaborative landscape management. We then invited people with knowledge and interest in agriculture, land management and conservation in Scotland to share their perspectives in a stakeholder engagement in June 2024. This involved two activities: 1) a consultation, via an online survey; and 2) a stakeholder workshop, held in person, in Perth on 25th June 2024. Each of these invited a range of stakeholders to respond to discussion questions, structured around a conceptual framework based on existing research about factors that support collaborative landscape management. Each engagement approach engaged 20 stakeholders. The survey was anonymous, so it is difficult to say precisely how many stakeholders contributed overall, but based on the organisations represented in each activity, we estimate around 30 stakeholders contributed overall. This yielded expert insights regarding lessons learned from experience of existing support for collaboration, as well as aspirations, needs, and interests of those involved in promoting and delivering collaborative landscape management. Below we first describe the conceptual framework, and then summarise the two stakeholder engagement activities, and how the resulting data were analysed.

Conceptual framework

A growing number of studies exist that identify and suggest factors that can contribute to supporting collaborative landscape management. These elements are brought together by Westerink et al. (2017), into a framework which suggests that to support collaborative landscape management, it is important to consider the following characteristics:

- Coordinating the collective effort of landholders across a landscape, and ensuring their efforts complement each other.

- Promoting the involvement of both governmental and non-governmental actors in processes of decision making around landscape management

- Enabling monitoring and learning from the effects of landscape management approaches

A range of specific factors have been suggested by various authors to help in enabling these characteristics (Hodge, 2024, Prager, 2015, Prager, 2022, Riley et al., 2018, Runhaar and Polman, 2018) These include:

- Building on existing relationships and collaborative activities.

- Skilled facilitation.

- Ensuring sufficient time, funding and resources are available, especially for facilitation.

- Setting clear and realistic expectations.

- Balancing top-down governance and bottom-up initiative.

- Navigating complex and contested interests and priorities.

- Learning, monitoring and knowledge exchange.

- User-friendly procedures for accessing incentives.

In this research, we used the above characteristics and specific factors to structure the questions for response in the consultation and discussion in the workshop, whilst remaining open-minded to responses emerging from beyond this framework.

Online consultation survey

The survey, administered online via Qualtrics, consisted of a mixture of open-ended and multiple-choice questions, which were structured around the factors that the conceptual framework identifies as important to consider for supporting collaborative landscape management. The open-ended questions asked stakeholders for their views on: supportive factors for collaborative landscape management; barriers to collaboration; the ideal roles of government and non-government actors; and understanding the impacts of collaborative activities. The multiple-choice questions asked stakeholders to rate how important they thought various factors would be in supporting collaborative landscape management, as well as how long they thought support should last for. The full list of questions is available in Appendix B.

In-person workshop

The workshop, held in-person at the Perth Subud Centre on 25th June 2024, brought together a group of 20 stakeholders to deliberate what was needed to support collaborative landscape management in a Scottish context. To provide a backdrop for the workshop discussions, the workshop began with a brief presentation by an academic expert on lessons for thinking about collaborative landscape management from elsewhere, followed by presentation of initial results from the online survey. Stakeholders were then asked to discuss the following set of four questions, based on the conceptual framework, in small groups, and list their responses:

- What is currently working well in terms of support for collaborative landscape management (drawing on examples from within Scotland and elsewhere)?

- What barriers exist for collaborative landscape management (drawing on examples from within Scotland and elsewhere)?

- In general, what types of support are needed to enable collaborative landscape management?

- How can learning and knowledge exchange about collaborative landscape management be supported?

The small group activity was followed by a full group session, in which stakeholders were asked to consider and discuss the question of how support for collaborative landscape management in Scotland could be done better, and then finally to note down suggested next steps. The full programme for the workshop is available in Appendix C

Recruitment of stakeholders

To recruit stakeholders for both the survey and workshop, we capitalised, initially, on contacts held by the research team with farmer clusters and non-governmental organisations working on biodiversity restoration and climate outcomes. We then expanded the selection through these networks, as well as via recommendations from Scottish Government partners. All of the stakeholders were invited to participate in both the survey and the workshop, though not all were able to participate in both. This resulted in a group of stakeholders who represented a range of different perspectives, including: farmers, farmer cluster facilitators, land agents, landowners, academic experts, and non-governmental organisations working in agriculture, land management and conservation. We also invited organisations involved in administering the Farm Advisory Service, but did not receive a response. Overall, 20 stakeholders participated in the survey and 20 (not all the same people) attended the workshop. These are listed in Table 1, below.

|

Sector represented |

Organisations |

|

Farmer clusters |

West Loch Ness Farm Cluster; Lunan Burn Wildlife Cluster; Strathmore Wildlife Cluster; Buchan Farm Cluster; Moray Farm Cluster |

|

Agri-environment NGOs |

Bioregioning Tayside; Linking Environment and Farming; South of Scotland Enterprise; ScotFWAG; Scottish Agricultural Organisation Society; Scottish Environment LINK; Leven Landscape Enterprise Networks |

|

Conservation NGOs |

SEDA Land; GWCT; RSPB Scotland; Forth Rivers Trust; Deer Management Groups |

|

Landowners/estates |

Crown Estate Scotland; Scottish Land and Estates |

|

Land agents |

Sylvestris |

|

Academic institutions |

The James Hutton Institute; University of Aberdeen |

|

Environmental agencies |

NatureScot |

|

Other |

Individual Consultant |

Overall, this stakeholder engagement included representation from a range of stakeholders involved in agriculture, conservation and land management. Existing farmer clusters, in particular, were well-represented, as were agri-environment and conservation NGOs. However, the tight targeting for this project meant that it was not possible for all possible stakeholders to be included. Perspectives from providers of farmer advisories could have been better represented, as could land agencies and the private sector. A UK Government General Election also hampered efforts to include perspectives from UK Government agencies involved in collaborative landscape management. The focus of the study on agriculture also meant that perspectives associated with other land uses, such as forestry and recreation, were not represented. The findings therefore strongly reflect farming and conservation perspectives and, whilst this is relevant to the agricultural reform programme, further studies may be enriched through inclusion of a wider range of perspectives.

Analysis

By design, both the survey and the workshop produced mainly qualitative data, regarding stakeholders’ views on what was needed to support collaborative landscape management. The data was collated by the research team into sets of summary notes, which we read through, carefully, and identified themes across the stakeholders’ responses. For rigour, we compared themes from the survey against those from the workshop, and from both activities against the proposed supportive factors for collaborative landscape management, identified in the conceptual framework. We also compared the themes across different groups of stakeholders, to explore if there was agreement/disagreement or difference between different sectors.

Limitations